The AI Product Builder’s Canon: The New Laws of Building AI Products

The 101 guide that explains the real machinery behind LLMs, diffusion models, embeddings, planning systems, autonomy, and the rise of a new kind of product management (and what you need to do).

If you ask ten PMs, five engineers, and two PhDs to explain what “AI” actually is, you’ll get ten incompatible diagrams, five contradictory definitions, two theoretical essays, and very little clarity.

Because most people working around AI understand the tools, not the structure behind the tools.

And when you don’t understand the structure, you make predictable mistakes:

Shipping features instead of systems.

Chasing model capabilities instead of designing model behavior.

Treating models as if they “know” things.

Assuming bigger models automatically deliver better outcomes.

Mistaking prompting for strategy.

Mistaking probability for intelligence.

Underestimating how damaging bad data truly is.

Choosing an LLM when a small supervised model would outperform it at 1% of the cost.

Blaming model architecture for what is actually a representation problem.

Let’s fix these today!

Chapter 1: The conceptual foundation of AI:

1.1 A First Principle: AI Is Not a Brain, It’s a Telescope

The most common but least useful analogy in AI is “the model is like a human brain.”

It isn’t.

A far better analogy: AI is a telescope.

A telescope doesn’t create stars. It reveals what is already there: filtered, amplified, and sometimes distorted.

AI does the exact same thing.

It reveals the structure of your data.

If your data contains deep, consistent patterns → the model magnifies them.

If your data contains contradictions → the model amplifies the contradictions.

If your data contains noise → the model tries to infer structure inside the noise.

When the telescope is pointed at cosmic emptiness, it shows you emptiness.

When pointed at chaotic light, it shows chaos.

When pointed at incomplete galaxies, your mind fills in the missing pieces.

That’s hallucination.

It’s not a bug. It’s a consequence of magnification under uncertainty.

Once you internalize this, every other AI behavior becomes predictable.

1.2. The Hierarchy of Intelligence: The Four-Layer Model

To make sense of the field, collapse its complexity into a layered stack.

Every model, technique, and concept fits into one of these four layers:

Representation – how information is encoded

Generalization – how patterns are learned

Reasoning – how patterns are recombined

Agency – how patterns lead to action

This hierarchy is the backbone of modern AI.

Layer 1 — Representation

Representation is the bedrock: how raw information becomes something a model can operate on.

Examples:

Text → tokens

Images → pixel arrays

Audio → spectrograms

Graphs → nodes and edges

User behavior → event sequences

Embeddings → geometric meaning

Representation determines what the model can “see.”

It also determines where the model will fail.

90% of the subtle bugs I’ve encountered across production systems trace back to representation issues:

wrong tokenization

poor embedding granularity

inconsistent formatting

missing modalities

incorrectly normalized inputs

Representation is the photographic plate of the telescope.

If it’s flawed, the model’s perception is flawed… no matter how advanced the architecture sitting on top of it.

Layer 2 — Generalization

This is where machine learning actually starts.

Generalization is the ability to learn patterns from incomplete, noisy, or imperfect data.

Every major method fits here:

Supervised learning finds patterns aligned with labeled truth.

Unsupervised learning finds structure without guidance.

Reinforcement learning finds strategies through reward and punishment.

Deep learning builds hierarchical patterns across multiple layers.

This layer contains:

Linear/logistic regression

Random forests

SVMs

k-means

PCA/ICA

CNNs

RNNs

Transformers

GANs

Diffusion models

But here’s the key insight:

Generalization is compression.

A model does not “understand.”

It compresses the structure in your data into parameters that can recreate or predict similar structure in the future.

Deep learning is simply compression with enough depth to encode extremely complex relationships.

The more compressible your domain, the better your model will perform.

Layer 3 — Reasoning

Reasoning isn’t a separate component you code into the model.

It emerges when pattern density becomes high enough.

Transformers enabled this by introducing a new mechanism:

Attention — the ability to dynamically focus on information across context.

From this mechanism emerges:

analogy

abstraction

chain-of-thought

explanation

synthesis

code generation

multi-step reasoning

LLMs do not reason because they have beliefs or goals.

They reason because information flows across layers in a way that encourages coherent recombination.

Instead of storing knowledge, they store geometry — high-dimensional structures representing relationships between concepts.

When you query the model, you traverse this geometry.

This explains both the brilliance and the instability:

When the geometry is dense → reasoning emerges.

When the geometry is thin → hallucination emerges.

Reasoning is geometry under constraints.

Layer 4 — Agency

This is where prediction becomes behavior.

An AI agent is simply a model augmented with:

memory

tools

goals

constraints

feedback loops

action space

When you give a model access to retrieval, APIs, file systems, specialized tools, planners, evaluators, or simulations, you cross into a new domain:

AI that acts, not just predicts.

Agency is where product decisions become architectural decisions:

How long should memory persist?

When should the agent ask for clarification?

How do you prevent runaway loops?

What tools should the agent use, and when?

How do you ensure safe failures instead of catastrophic ones?

The companies who understand agency are already building the next generation of software.

The companies who treat models as autocomplete are falling behind without realizing it.

1.3. Why LLMs Feel Magical… and Why They’re Misunderstood

Despite their complexity, LLMs follow the same fundamental process as simpler ML models:

They map inputs to outputs by minimizing a statistical objective.

The magic comes from the scale and structure, not from a fundamentally new type of intelligence.

Here’s how different model classes compare:

Model Type → What It Captures→ Why It Fails

Linear/logistic regression → one direction of variation → too shallow

Random forest → many shallow patterns → no abstraction

CNN → spatial patterns → limited global reasoning

RNN → sequential patterns → short memory

Transformer → global relationships → dependent on context

LLM → dense world models → dependent on data coverage

LLMs feel intelligent because when trained on trillions of tokens, they begin to encode:

human intentions

domain logic

cause-effect relationships

analogies

planning heuristics

latent models of the world

Not perfectly — but sufficiently well to mimic reasoning.

This doesn’t make them conscious.

It makes them statistically powerful.

Once you internalize this, you stop over-attributing intelligence and underestimating failure modes.

1.4. Deep Learning: The Symphony Behind the Wall

Deep learning is often explained through neurons, backpropagation, or mathematical optimization.

Let’s replace all of that with something more intuitive and more accurate.

Imagine trying to reconstruct an entire symphony by listening to millions of concerts through a wall.

You never hear the music clearly. You hear vibrations — repeated patterns of rhythm, harmony, cadence.

Over time, your brain infers:

the structure

the instruments

the progression

the emotional arcs

Not because you learned music theory, but because you absorbed statistical regularities.

This is how models learn:

They never see truth directly.

They infer it through repeated exposure.

They compress it into parameter space.

If you feed them inconsistent music, they learn inconsistent music.

If you feed them noise, they search for patterns inside the noise.

If you feed them incomplete data, they hallucinate to fill the gaps.

This analogy explains more about model behavior than 100 slides on backpropagation.

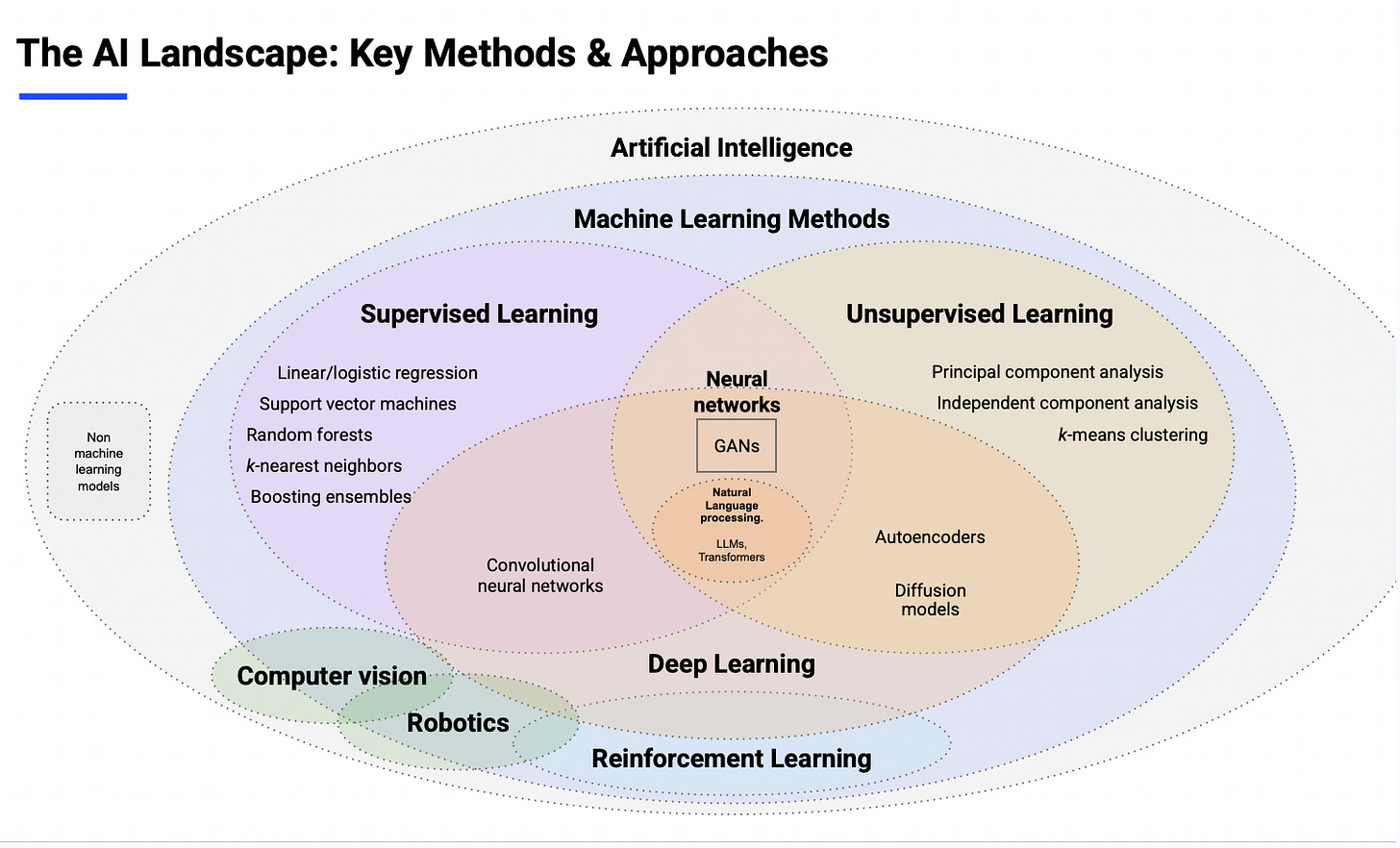

1.5. Reinterpreting the AI Landscape Diagram

Traditional diagrams separate AI into:

supervised learning

unsupervised learning

reinforcement learning

deep learning

neural networks

NLP

vision

robotics

But these aren’t separate universes.

They’re evolutionary steps.

A better way to view the progression:

Statistics → shallow patterns

Machine Learning → structured patterns

Neural Networks → hierarchical patterns

Transformers → global patterns

LLMs → world models

Agents → action

Each layer extends the previous one.

None of them truly disappear.

The diagram you started with is the “map.”

This hierarchy is the “terrain.”

AI PMs who only understand the map get lost.

Builders understand the terrain.

1.6. Two Laws Every AI Product Builder Learns Over Time

Law 1: The model is a mirror of its data.

No amount of prompting, filtering, or scaling compensates for flawed data representations.

Evaluation pipelines matter more than parameter count.

Law 2: A model is not real until it survives deployment.

In production, you encounter:

drift

adversarial inputs

long-tail failures

latency constraints

user misuse

incomplete context

malformed inputs

unpredictable edge cases

Training gives you theoretical performance.

Deployment gives you actual behavior.

1.7. The Core Insight: AI Systems Fail for Conceptual Reasons, Not Technical Ones

Most AI product failures come from strategic misunderstandings, not engineering mistakes.

Failures arise when teams:

misuse the wrong class of models

treat stochastic systems like deterministic ones

underestimate context management

overestimate generalization

ignore data provenance

skip evaluation loops

conflate capability with value

Great AI products come from teams who understand the behavior of models under uncertainty, not just their architecture on paper.

This is the difference between shipping a feature and architecting an intelligent system.

This newsletter deep dive is brought to you by Product Faculty’s AI Product Management Certification.

The #1 program taught by OpenAI’s Product Lead, trusted by 3,000+ PMs, with 740+ reviews on Maven.

If you want to master building AI products from scratch, learn a complete end-to-end system (Discovery → Design → Development → Deployment), walk away with your own portfolio-ready AI product, and future-proof your career… this cohort is for you.

»»»» Click here to get $500 off before enrollment closes.

Chapter 2 — The Foundations of Machine Learning: Supervised, Unsupervised & Reinforcement Learning

Most people learn supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning the way you learn the periodic table in high school: as isolated categories to be memorized rather than systems to be understood.

But when you’ve actually trained models: when you’ve watched them overfit, collapse, diverge, saturate, destabilize, plateau, or misbehave…

… You start seeing these three learning paradigms not as boxes but as different ways of making the world predictable.

They’re not “methods.” They’re philosophies of learning.

The Three Learning Paradigms Are Three Different Answers to One Question

Every machine learning system answers a single fundamental question:

“Given the information I have, what is the most useful pattern I can learn?”

The three learning paradigms differ only in what “information” means:

Paradigm → The Model Gets → The Model Tries To Learn

Supervised → Inputs + correct outputs → The mapping between them

Unsupervised → Inputs only → The structure hidden inside them

Reinforcement → Inputs + rewards for actions → A strategy that maximizes reward

They are three ways intelligence can emerge: by imitation, by discovery, anf by trial and error

Let’s explore each through the builder’s lens.

2.1. Supervised Learning ( The Art of High-Fidelity Imitation)

Supervised learning is the simplest to describe and the most misunderstood.

It’s where the model tries to mimic a mapping between X → Y:

Image → label

Text → category

Customer history → churn probability

Sensor signals → anomaly score

Sentence → sentiment

Email → spam/ham

But this simplicity hides something important:

Supervised learning does not create intelligence.

It creates consistency.

A supervised model learns to behave like its dataset.

This is both its greatest strength and its Achilles heel.

Supervised Learning Is Apprenticeship

Imagine training a carpenter by giving them:

thousands of chair blueprints,

the final assembled chairs,

and the instruction:

“Make the next one look like these.”

Supervised learning works the same way.

If your dataset contains:

elegant chairs → elegant models

poorly built chairs → poorly built models

inconsistent chairs → inconsistent models

biased chairs → biased models

The model mirrors the dataset’s craftsmanship… or lack of it.

This is why the real work in supervised learning isn’t tuning the model.

It’s tuning the teachers: the data, labels, distributions, and edge cases the model imitates.

The Hidden Complexity: Labels Are Not Truth, They Are Opinions Frozen in Data)

Most PMs assume labels = ground truth.

Engineers know better.

Labels are:

approximations

judgments

heuristics

artifacts of human perception

sometimes contradictions

When you train on messy labels, your model becomes a paradox: a flawlessly learned representation of flawed human decisions.

This is why model evaluation often reveals disagreements even humans can’t settle.

It’s not the model failing.

It’s the data revealing its own ambiguity.

Why Supervised Learning Fails in Production

Supervised models are brittle because they learn correlation, not causation.

A model trained to classify “husky vs. wolf” famously learned the presence of snow in the background — because most wolf photos had snow.

In real products, I’ve seen supervised models latch onto:

lighting artifacts

annotation glitches

timestamp leakage

user behavior proxies

bugs in upstream systems

Not because the model is “wrong,” but because it’s too good at finding shortcuts.

Supervised learning is powerful only when:

the labels are meaningful

the data distribution is stable

the environment is predictable

This is rarely the case in live systems.

2.2. Unsupervised Learning (The Art of Discovering Structure)

Unsupervised learning is where the model tries to understand the world without a teacher.

You give the model only X, no Y.

And ask it: “What structure do you see?”

Clustering, dimensionality reduction, density estimation, embeddings — these techniques don’t classify; they organize.

Unsupervised Learning Is Cartography

If supervised learning is apprenticeship, unsupervised learning is mapmaking.

Give an unsupervised model:

10,000 songs → It discovers genres.

10 million documents → It discovers topics.

1 billion user clicks → It discovers user segments.

100,000 images → It discovers visual motifs.

It builds the map of the territory before anyone tells it where the borders are.

This is why unsupervised methods often feel magical to beginners.

But any builder knows: unsupervised models don’t discover “truth.”

They discover useful axes of variation.

They reveal how the data clusters in practice, not how it “should” cluster.

This distinction matters.

PCA, ICA, t-SNE, k-means…

Here’s how a practitioner sees them:

PCA → “Find the directions where the data stretches the most.”

ICA → “Separate the overlapping sources of variation.”

k-means → “Group things that look like each other.”

DBSCAN → “Find the dense neighborhoods.”

Autoencoders → “Compress the world into a bottleneck and reconstruct it.”

These techniques are not magic. They are lenses.

Change the lens → change the structure you see.

This is why unsupervised learning is so dangerous in the hands of PMs who don’t understand data distributions.

You can accidentally create:

artificial clusters

meaningless segments

unstable embeddings

phantom patterns

The model isn’t wrong, your lens is.

Representation Learning

The true breakthrough of unsupervised learning is not clustering.

It’s representation learning: the art of converting messy real-world data into dense vectors that capture its meaning.

Embeddings are the Rosetta Stone of modern AI.

They let models compare search, summarize, retrieve, etc.

Not by metadata, but by meaning.

LLMs, semantic search, RAG, memory systems, agent context retrieval… none of these exist without good representation learning.

In practice, every advanced AI system is built on the shoulders of unsupervised representations.

2.3. Reinforcement Learning (Learning Through Consequences)

Reinforcement learning (RL) is the most human-like form of machine learning because it mirrors how we learn as children:

Try something

Observe the consequence

Update your behavior

Try again

An RL model doesn’t learn from examples. It learns from experience.

Reinforcement Learning Is Survival in an Unknown World

Imagine dropping an explorer into a new continent.

No maps. No signs. No teachers.

Only one rule: “Do more of what keeps you alive. Do less of what doesn’t.”

This is RL.

The agent tries random actions at first. Most fail. Some succeed.

The agent remembers the successes and builds a policy around them.

Over time:

Randomness becomes strategy.

Strategy becomes instinct.

Instinct becomes optimal behavior.

This is why RL solves problems supervised learning can’t:

robotics

game-playing

navigation

sequential planning

tool use

long-horizon decision-making

RL Is Unstable, Fragile, and Expensive

No senior AI engineer will deny it.

RL training: explodes, collapses, saturates, oscillates, diverges, gets stuck in local minima, AND requires massive exploration!

In supervised learning, you optimize a fixed objective: “Predict Y accurately.”

In reinforcement learning, you optimize a shifting landscape of behavior.

This makes RL magical when it works and nightmarish when it doesn’t.

RLHF — Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

Most PMs know RLHF from LLMs, but few understand what it actually does.

RLHF teaches models:

social norms

conversational boundaries

politeness

helpfulness

refusal behavior

risk aversion

Through human preference signals (reward models), not labels.

The model doesn’t learn facts. It learns what humans like.

That distinction matters more than people think.

When a model “refuses,” it’s not because it believes something is dangerous.

It’s because it learned that humans reward refusals in certain contexts.

RLHF doesn’t install morality.

It installs policy.

How the Three Paradigms Work Together

Every real AI system uses all three paradigms at once.

Here’s how they stack in production:

Unsupervised learns representations.

Supervised shapes them into useful predictions.

Reinforcement teaches them to act in the world.

LLMs highlight this perfectly:

pretraining → unsupervised learning

finetuning → supervised learning

alignment → reinforcement learning

This trifecta is the engine behind modern intelligence.

Any one alone is insufficient.

Together, they form a self-reinforcing system: discover → imitate → adapt → act

This is the lifecycle of intelligence… human or artificial.

2.4. The Practical Takeaways

Takeaway 1: Choose the paradigm based on the uncertainty in your environment.

Stable world → supervised.

Unknown world → unsupervised.

Interactive world → reinforcement.

Most failed AI projects use the wrong paradigm.

Takeaway 2: Unsupervised learning is where differentiation is built.

Your embeddings, clusters, and representations are the moat.

Not the predictive model on top.

Takeaway 3: Reinforcement learning requires guardrails.

Never deploy RL without:

constraints

safety limits

monitoring

rollback mechanisms

Agents will exploit loopholes ruthlessly: sometimes hilariously, sometimes catastrophically.

Takeaway 4: Supervised models inherit all human biases in the labeling process.

Bias is not a model problem. It’s a data process problem.

Takeaway 5: The real skill is combining paradigms, not choosing one.

Modern AI systems win by designing pipelines, not models.

CHAPTER 3 — The Machinery of Thought: Neural Networks, CNNs, RNNs & Transformers (How Hierarchy Becomes Intelligence)

If supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning give us three philosophies of how machines learn, then neural networks give us the machinery through which those philosophies materialize.

And it’s here — in the messy, layered, often counterintuitive mechanics of networks — that you begin to see how simple mathematical functions, stacked and trained in large numbers, can begin to approximate something startlingly close to reasoning.

Most explanations of neural networks begin with the neuron abstraction: weights, bias, activation…

But in my personal opinion… it’s a misleading starting point. Because the individual neuron explains nothing about why deep learning works… only when you stack neurons into layers, and layers into hierarchies…

… And hierarchies into architectures that allow information to compress, recombine, distort, amplify, and ultimately abstract itself into higher-order meaning.

So let’s begin not with the neuron, but with the larger truth:

A neural network is a machine for learning representations, and all of its intelligence emerges from the geometry of those representations, not from the individual components inside it.

This is important. Because it means the power of the network comes not from what it is, but from what it can become under a learning process.

3.1. The Neural Network as a Pipeline of Transformation

Imagine passing an object through a series of lenses, each lens altering the object just slightly and by the time the object passes through a dozen such lenses…

It is no longer recognizable, yet all of its essential structure is preserved in a reconfigured form that is easier to work with.

This is what a neural network does.

Each layer performs a simple linear transformation, followed by a non-linear twist, which prevents the entire system from collapsing into a single linear mapping.

You can think of the layers as filters that progressively extract higher-level abstractions from raw data.

In images:

early layers detect edges

middle layers detect shapes

late layers detect semantic objects

In text:

early layers detect syntax

middle layers detect phrase structure

late layers detect meaning, intent, reasoning patterns

This idea — that hierarchy leads to abstraction, and abstraction is the substrate of intelligence — is the central organizing principle behind all deep learning.

It is also the reason shallow models fail: without depth, you cannot create abstraction.

And without abstraction, you cannot generalize.

And without generalization, you cannot reason.

3.2. CNNs — The Eyes of the Machine

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were the first architectures that truly shocked the world, because for the first time machines could see in a way that was structurally aligned with how humans see… not by memorizing pixels, but by extracting spatial hierarchies.

A CNN works by scanning small filters (kernels) across an image, looking for recurring visual motifs, and then gradually assembling them into larger concepts.

Here’s the key insight most people never internalize:

CNNs do not understand images; they understand stability in local patterns.

If a cat’s ear shifts two pixels left, a CNN doesn’t panic, because spatial invariance is built into the structure.

If the lighting changes, or the orientation shifts slightly, CNNs can still recover the object, because they are learning the essence of patterns, not their exact locations.

But they fail when the world deviates too far from their training distribution, because CNNs, despite their elegance, are fundamentally short-range thinkers — they excel at local structures but struggle with long-range dependencies.

A CNN can recognize a face.

It cannot infer the story behind the face.

That requires a deeper form of structure.

3.3. RNNs — The Memory That Was Never Enough

Before Transformers, sequential data was the territory of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and although RNNs were an important bridge in the evolution of AI, their influence is fading, not because they were flawed, but because the world demanded more than they could offer.

RNNs process information one step at a time, feeding hidden states forward like a chain of whispers in a crowded room, and just like real whispers, the message deteriorates or vanishes entirely as the sequence grows long.

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and GRUs improved the situation by creating gated pathways that allowed information to persist longer, but even these architectures struggled with:

extremely long sequences

distant dependencies

complex reasoning over large contexts

When you train RNNs in practice, you see this limitation viscerally — loss curves that oscillate, gradients that vanish, context that evaporates, predictions that become increasingly noisy the longer the sequence gets.

The model is trying to remember a sentence while forgetting the beginning as it processes the end.

You cannot expect deep reasoning from a system that forgets its own thoughts while thinking them.

RNNs were a necessary step, but not the final step.

3.4. Transformers: The Architecture That Changed Everything

The Transformer architecture solved the core problem limiting previous models:

the inability to reason over long contexts.

It did this not by adding memory, nor by deepening recurrence, but by eliminating recurrence entirely and replacing it with a mechanism that feels almost alien in its simplicity:

Attention — the ability for any token to directly observe any other token, regardless of distance.

In one stroke, the model gained an ability no previous architecture had:

global visibility.

This global visibility is where reasoning begins.

Let’s break down why.

3.5. Attention — The Mechanism That Feels Like Thought

Attention allows each token to ask three implicit questions:

Who am I?

Who matters to me right now?

How should I incorporate them into my next representation?

These are not metaphors; they are algebraic operations.

But the emergent effect feels almost cognitive.

The attention mechanism creates a dynamic interaction graph between all elements of the input.

Instead of compressing context into a single hidden state like RNNs, the Transformer distributes context across many parallel layers where every step of reasoning can be reconstructed from scratch using the entire sequence.

This is why Transformers can:

stay coherent over long narratives

solve analogies

follow multi-step reasoning

manipulate symbolic structures

write code

translate meaning rather than syntax

maintain global constraints in text

If CNNs gave models eyes, and RNNs gave them short-term memory, Transformers gave them an internal canvas where ideas can interact at arbitrary distances.

3.6. The Geometry of Language

When you train a Transformer at scale, the model begins organizing concepts into geometric relationships in extremely high-dimensional space.

This geometry becomes a kind of internal physics:

synonyms become neighbors

analogies become parallel directions

abstractions become attractor basins

contradictions become unstable regions

domain shifts become distortions in local curvature

And once this geometry stabilizes, something extraordinary happens:

Reasoning emerges as the traversal of geometric structures.

It’s not logic in the human sense; it’s not symbolic planning; it’s not truth tables or rules.

It is movement through meaning-space, guided by statistical optimization but shaped by the latent structure of the dataset.

This explains:

why LLMs can write poetry

why they can fix bugs in code

why they sometimes hallucinate

why they sometimes refuse

why they sometimes think in analogies instead of direct answers

why they generalize so well across tasks they were never explicitly trained for

The model is not recalling memorized facts.

It is traveling through a learned landscape of relationships.

3.7. Why Transformers Destroyed Everything Before Them

Once attention-based architectures appeared, the limits of CNNs and RNNs became painfully clear.

CNNs failed at long-range relationships.

RNNs failed at remembering what they already processed.

Transformers failed at neither.

And so the field pivoted — not out of fashion, but out of inevitability.

Everywhere that sequential understanding mattered, Transformers outperformed.

Everywhere that abstraction mattered, Transformers outperformed.

And when scaled, they didn’t just outperform — they transformed the field, because they revealed something the AI community hadn’t fully appreciated:

When you give a sufficiently expressive architecture enough data and compute, intelligence begins to look like an emergent property rather than an engineered one.

This was the paradigm shift.

We stopped designing intelligence and started growing it.

3.8. The Fragility Beneath the Brilliance

Despite their power, Transformers are not invincible — and anyone who has trained them knows the numerous ways they can implode.

They are:

sensitive to data distribution

prone to overfitting subtle artifacts

easily derailed by malformed input

computationally expensive

memory-hungry

brittle under domain shift

unreliable at the extremes of context length

A model may appear coherent for 800 tokens, then unravel into contradictions, self-interruptions, or non sequiturs at 801, because the geometry is stretched beyond the region in which it was learned.

Transformers are brilliant… but they are brilliant within their learned boundaries.

Outside those boundaries, they behave like any other statistical system: creatively but incorrectly.

This is not a failure of intelligence.

It is a reminder of its constraints.

Here is the mental model I actually use when designing systems:

Neural Networks → abstraction machines

CNNs → perception machines

RNNs → sequence machines

Transformers → reasoning machines

But this hierarchy is not about superiority.

It’s about expressiveness.

As the architecture gains the ability to represent more complex relationships, it gains the ability to perform more sophisticated cognitive functions.

A Transformer is not “smarter” than a CNN.

It simply sees further, combines ideas more flexibly, and retains context over distances CNNs and RNNs cannot handle.

CHAPTER 4 — How Machines Imagine: Diffusion Models, GANs, Embeddings & The Geometry of Meaning

In the previous chapters, we learned how machines perceive (CNNs), remember (RNNs), and reason (Transformers), now this chapter explains how machines imagine… and this requires an entirely different kind of intelligence.

Because imagination is not about predicting the next token or classifying an input, but about generating something that has never existed before while still feeling anchored in the structure of the real world.

Human creativity operates in a tension between familiarity and novelty… you compose a melody no one has heard, but it still follows harmonic patterns that resonate with the listener; you sketch a face that doesn’t exist, but its geometry feels plausible enough to belong to a real person; you write a sentence that is original but coherent.

Generative models must operate in that same tension.

And to understand how they do it, we need to explore three pillars:

GANs — adversarial imagination

Diffusion models — denoising imagination

Embeddings — geometric imagination

Together, they give machines the capacity to create, refine, compare, interpolate, and navigate complex meaning spaces.

4.1. The Strange Genius of GANs — Imagination Through Adversarial Tension

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) were the first models to produce images that felt undeniably real, and when you train one yourself….

When you watch the generator stumble through the early epochs, hallucinating grotesque blobs of pixels, until suddenly a face appears with eyes and skin and hair…

You witness something that feels more like evolution than optimization.

GANs are built from two networks locked in a zero-sum game:

the Generator (G) tries to create synthetic data

the Discriminator (D) tries to detect fakes

The generator improves by learning to fool the discriminator;

the discriminator improves by learning not to be fooled.

This adversarial loop creates a feedback cycle in which both sides sharpen each other.

But the deeper truth is this:

GANs learn to imagine by learning how not to be caught.

The generator is never directly told what a “good image” is; it only learns what the discriminator cannot distinguish from reality, which means GANs are essentially trained to exploit the discriminator’s blind spots.

This produces uncanny results:

faces with perfect symmetry

textures with impossible smoothness

patterns that “look right” but fall apart under close inspection

GANs don’t learn the world; they learn the weaknesses in the model that represents the world.

They are creators shaped by critics.

The Instability: Why GANs Are So Hard to Train

Anyone who has trained GANs knows the journey is violent.

The model oscillates wildly:

sometimes the generator collapses to a single output

sometimes the discriminator becomes too strong and learning stops

sometimes both networks diverge

sometimes they enter a chaotic loop of generating nonsense

GANs are not stable because adversarial games are not stable.

And yet, their instability is what made them magical in the first place.

GANs showed us that creativity emerges not from precision, but from tension…. the same way human artists improve when they face genuine critique.

But GANs weren’t the architecture that truly unlocked generative modeling.

Their successors — diffusion models — brought a level of stability and fidelity GANs could never reach.

4.2. Diffusion Models — Imagination Through Denoising

Diffusion models learn to imagine in a profoundly counterintuitive way: they learn by destroying images.

A diffusion model repeatedly adds noise to an image until it becomes pure static, then learns the reverse process: how to remove noise step by step to reconstruct the original image.

Over millions of iterations, the model doesn’t just learn how to “clean up noise”; it learns the deeper structure that defines the image category:

the distribution of edges

the geometry of objects

the texture of skin

the symmetry of faces

the color correlations of landscapes

It learns a kind of image physics — rules about how the world tends to look — and because of this, diffusion models can generate stunningly realistic outputs by simply starting with random noise and guiding the denoising process toward a desired outcome.

Here’s the conceptual leap:

If GANs generate by confrontation, diffusion models generate by reconstruction.

GANs ask: “How can I fool you?”

Diffusion models ask: “How do I transform noise into structure?”

The second question produces more stable, higher-quality results.

Why Diffusion Models Feel So Natural

The secret behind diffusion’s success is that the world is filled with gradual transitions, not discrete jumps.

A face ages gradually.

A cloud forms gradually.

Light transitions gradually.

Textures spread gradually.

Diffusion captures this continuity.

It creates images by simulating a process that resembles physical evolution:

coarse structure emerges

mid-level details form

fine-grained textures resolve

color gradients converge

This staging makes diffusion models far more interpretable to the human eye and far more controllable for model builders, because each step in the denoising process can be conditioned on: text embeddings, style vectors, masks, depth maps, and segmentations.

This is why models like Stable Diffusion and DALL·E feel like controllable engines of creativity rather than chaotic adversarial generators.

Diffusion doesn’t fight to imagine. It unveils imagination.

4.3. Embeddings — The Geometry of Meaning

If GANs create and diffusion models refine, embeddings organize.

Embeddings are perhaps the most foundational, most misunderstood, and most important concept in modern AI systems.

An embedding is a point (or vector) in high-dimensional space representing: a word, a sentence, an image, a user, a product, a latent feature of the world, etc.

But the power of embeddings is not in the vector itself.

It’s in its relationships.

What matters is distance:

similar objects cluster

dissimilar objects repel

analogies align along linear directions

hierarchies compress into geometric gradients

This is the closest thing we have to a computational theory of meaning.

Embeddings Are Coordinates in the Landscape of Thought

Imagine that every concept in the world — “dog,” “loyalty,” “running,” “freedom,” “forest,” “algorithm,” “sadness” … lived somewhere on a vast, invisible map.

You cannot see the map.

You can only measure distances.

But those distances encode everything:

words near each other share meaning

sentences that point in the same direction share intent

images that cluster share latent attributes

users that cluster share preferences

Embedding space is not linguistic.

It is conceptual.

This is how models “know” that:

Paris is to France as Berlin is to Germany

A corgi and a German shepherd are both dogs

“How to cook rice” is similar to “best way to boil rice”

A user who likes minimalist interior design may also like Japanese architecture

But embeddings do something even more remarkable.

Interpolation ( The Secret Superpower of Embedding Space)

When two concepts live in a geometric space, you can interpolate between them.

Humans do this all the time subconsciously:

imagining a hybrid animal

blending two music genres

creating metaphors

transitioning between moods

designing products that merge aesthetics

AI models can do this explicitly.

Give the model embeddings for a cat or a dragon…

The space between them is filled not with noise, but with the meaningful morphing of attributes: feline → reptilian, fur → scales, and whiskers → horns.

Diffusion models exploit this for image synthesis.

LLMs exploit it for ideas.

Recommendation engines exploit it for taste prediction.

Agents exploit it for planning.

Interpolation is where creativity emerges.

It is the ability to travel between ideas.

What Embeddings Reveal About Intelligence

When you work with embedding systems long enough, you eventually realize something that changes how you think about AI entirely:

Intelligence is not stored in rules or symbols, it is stored in geometry.

The model doesn’t store facts. It stores relationships.

It doesn’t store grammar. It stores patterns of co-occurrence.

It doesn’t store images. It stores distributions of texture, edges, color, and form.

Meaning itself becomes a physical structure in the model.

This is why LLMs can reason through analogy even though they weren’t explicitly trained to “do analogies.”

Analogy is simply a geometric transformation.

And this is why diffusion models can generalize to styles they’ve never seen:

style is a direction in latent space.

Once meaning becomes geometry, imagination becomes navigation.

4.4. How These Systems Power Modern Generative AI

All generative AI systems you see today operate through a combination of:

vector geometry (embeddings)

iterative refinement (diffusion)

pattern synthesis (Transformers)

adversarial sharpening (GANs, or discriminator-like critic networks)

This fusion creates an engine capable of:

constructing ideas

deconstructing noise

bridging modalities

translating images ↔ text

performing controlled generation

reasoning visually and linguistically

creating coherent worlds

The key insight is this:

Generative AI does not generate from scratch; it generates by navigating, recombining, and refining the geometry of learned structure.

There is no blank canvas.

There is only a vast latent universe waiting to be explored.

4.5. Why This Matters for AI Product Builders

If you’re building real systems, here are the truths that matter:

Truth 1 — All creativity is constrained by representation.

A model cannot create beyond the geometry it has learned.

Truth 2 — Diffusion is controllable; GANs are expressive but unstable.

Choose your architecture based on your reliability needs.

Truth 3 — Embeddings decide what the model “thinks” is similar.

Your entire product’s UX can hinge on vector space alignment.

Truth 4 — Interpolation is the engine of personalization.

Products don’t need to know the user; they only need to know the user’s coordinates.

Truth 5 — Generative AI is not a model problem; it’s a system design problem.

It requires: retrieval, conditioning, post-processing, prompt engineering, constraints, and evaluators.

Generative systems are not black boxes. They are pipelines.

And the companies that understand this will own the next decade of AI product innovation.

Chapter 5 — When Intelligence Begins to Act: Agents, Tool Use, Memory & Planning Systems

This chapter explains the final frontier: how machines begin to behave, and how behavior - whether in a small task-oriented agent or a large multi-step autonomous system.

It all emerges from the interplay between reasoning, memory, tools, and constraints.

Most people assume that “agents” are simply LLMs wrapped in loops, but anyone who’s built real autonomous systems knows that an agent is not a wrapper, but an architecture for decision-making under uncertainty.

And the moment you give a model the ability to take actions — even trivial ones, like calling an API or writing to a file — you leave the territory of generative modeling and enter the domain of behavioral control, which is far closer to robotics, economics, and cognitive science than to NLP.

So before we go into the mechanics, let’s begin with the conceptual truth:

Prediction is cheap.

Behavior is expensive.

And autonomy is not intelligence, autonomy is responsibility.

Once you understand that, you start designing very differently.

5.1. What Is an Agent?

An agent is a system that does three things:

Observes the world (through input, retrieval, or state).

Decides what to do (through reasoning, planning, or heuristics).

Acts on the environment (through tools, APIs, or physical actuators).

In other words: An agent = observation + cognition + action.

And because every action changes the environment, which then changes future observations, agents operate not in static problems but in dynamical systems: systems where error, drift, misalignment, instability, and compounding consequences can happen quickly.

To design an agent well, you must design the world it lives in, its: sensory channels, memory boundaries, reward structures, error surfaces, guardrails, action limits, etc.

Agents require ecosystems, not just models.

The Evolution of Tool Use — From Language Models to Systems That Can Act

Language models do not naturally “use tools.” They generate text. That is all they were trained to do.

So when we give them tools, we are not giving them new abilities; we are giving them new interfaces through which their text outputs can influence the world.

A tool call is just a structured sentence that says:

“Search Google for X.”

“Query the database.”

“Write file Y.”

“Call API Z.”

But when an LLM learns how to choose between tools, sequence them, and evaluate outcomes, it becomes capable of performing tasks that would otherwise require entire teams.

The leap is subtle but profound: A model becomes an agent when language becomes intention, and intention becomes action.

Most people don’t realize how fragile this leap is.

Memory — The Agent’s Sense of Time

A non-agentic LLM is timeless. It has no past.

It has no state.

It is a mind with no continuity.

Agents, however, require temporal coherence, which means they must:

remember prior steps

recall decisions

track goals

integrate feedback

update plans

avoid repeating errors

Memory systems are what turn an LLM from a one-shot oracle into a consistent collaborator.

There are several kinds of memory:

Short-term ephemeral memory → working context window

Long-term episodic memory → vector databases, retrieval logs

Procedural memory → learned behaviors encoded in weights

Semantic memory → world knowledge, ontologies

Self-reflective memory → previous decisions, errors, strategies

The hardest part is not building memory — it’s selecting the right memory.

Too much memory → hallucination, overfitting, distraction.

Too little memory → repetition, lost goals, broken chains of reasoning.

A well-designed agent doesn’t store everything.

It stores what improves its future behavior.

Planning — The Missing Ingredient Most Agents Lack

Most agent frameworks today are primitive because they rely on a naive loop:

Model proposes an action

Execute it

Ask the model what to do next

This creates shallow behavior: reactive, local, myopic.

But intelligent behavior requires planning, which is the ability to map a sequence of actions toward a goal, evaluate alternative paths, anticipate failures, and adjust course.

Planning architectures include:

forward search

model-based reasoning

Monte Carlo tree exploration

hierarchical task decomposition

chain-of-thought with verification

program synthesis

simulation-based rollout

But the truth is simpler:

Planning is the art of turning goals into sequences.

Bad agents know what to do next.

Good agents know what they are doing next and why.

Great agents know what they are doing several steps from now.

And in high-risk environments — robotics, finance, medical decisions — this distinction is life and death.

Acting Safely — Why Autonomy Is a Constraint Problem, Not a Capability Problem

Giving an agent the ability to act sounds powerful, but in practice it is dangerous, because the space of possible actions is always larger than the space of correct actions.

A safe agent is one that:

cannot take irreversible actions without verification

cannot escalate privileges

cannot access tools without constraints

cannot make silent failures

cannot bypass policy

cannot infinitely recurse

cannot destroy its own context

cannot misinterpret ambiguous goals

The moment an agent has write permissions — to a document, a file, an API, or a physical robot — you enter safety-critical territory.

Builders learn this lesson quickly: Most agent failures do not come from the model.

They come from the environment and the lack of constraints around the model.

The Four Failure Modes of Agents (Every Builder Encounters These)

1. Hallucinated Actions: The model invents tools, states, or APIs that do not exist.

2. Infinite Loops: The agent continues reasoning without terminating.

3. Goal Drift: The agent subtly changes the task as it attempts to complete it.

4. Over-Confidence Errors: The agent executes an irreversible action with high confidence but low competence.

You do not eliminate these failures, you design around them:

strict tool schemas

validation layers

external evaluators

simulation environments

reward shaping

guardrails and ceilings

Agents are not safe by nature.

They are safe by design.

5.2. Multi-Agent Systems — When Behavior Emerges From Interaction

One agent can perform a task.

Two agents can collaborate.

But dozens of agents interacting begins to create emergent properties.

In multi-agent systems, agents can: debate, critique, specialize, negotiate, divide labor, evaluate each other, refine and combine plans, and solve problems no single agent could solve alone.

This mirrors human organizations, where intelligence is distributed across people, systems, and structures.

But multi-agent systems also inherit new risks:

coordination failures

echo chambers

runaway reinforcement

adversarial interference

collusion

instability in feedback loops

A multi-agent system is not just an algorithm, it’s a micro-society.

And it must be governed like one.

5.3. Agents & Tool Use in Real AI Products

Every robust AI product today increasingly looks like an agentic system:

Notion AI uses retrieval + tool calling.

GitHub Copilot uses code execution feedback loops.

ChatGPT uses system-level tool orchestration.

Claude uses structured reasoning with function calls.

Perplexity uses multi-agent retrieval and synthesis.

The winning products are not the ones with the biggest models.

They are the ones with the best agent architectures: the cleanest loops, the best evaluators, the strongest constraints, and the clearest reward structures.

If traditional apps were CRUD systems (create, read, update, delete), AI-native apps are ARC systems:

Act

Reason

Correct

The future belongs to systems that can:

diagnose themselves

fix their own mistakes

evaluate their own outputs

plan their own tasks

and justify their decisions

This is autonomy with accountability.

The Builder’s Principle: “An Agent Is a Contract, Not a Model.”

Whenever I design an agent, I write the contract before writing the architecture:

What must the agent never do?

What must the agent always do?

What tools can it access?

What is outside its domain?

What is its reward structure?

What is its failure surface?

What constraints protect the environment from the agent?

What constraints protect the agent from the environment?

A model generates text.

An agent generates consequences.

It must operate under a social, ethical, and technical contract — one that developers, organizations, and sometimes entire societies agree upon.

CHAPTER 6 — The Physics of Large Models: Scaling, Emergence, Alignment & Failure Modes

There is a moment that every AI builder remembers vividly: the moment a model becomes qualitatively different from its smaller versions, when the increase in capability cannot be explained by “more parameters” or “more data,” when something unexpected emerges that was not programmed, not anticipated, not explicitly trained.

For some, it happened with GPT-2; for others, with GPT-3; for many more, with the largest instruction-tuned models today.

But the emotional experience is the same: You interact with the model, expecting stochastic autocomplete, and suddenly it begins to display reasoning patterns so coherent, so structured, so context-sensitive that you feel… for a moment… that you are speaking to something that is doing more than predicting tokens.

This moment is not magical.

It is scaling law physics.

It is emergence.

And once you understand emergence, you begin to understand why the old intuitions — about model size, data, safety, control, planning, abstraction — all break down.

6.1. Scaling Laws — The Statistical Gravity That Shapes Intelligence

Large language models follow surprisingly predictable scaling laws: as you increase model size, dataset size, and compute, you observe inverse power-law improvements in:

perplexity

accuracy

reasoning depth

abstraction

generalization

error correction

world modeling

This is not a coincidence.

It is the statistical equivalent of gravity: the more you scale, the smoother the loss landscape becomes, and the easier it is for gradient descent to find high-quality solutions.

Here’s the non-obvious truth:

Intelligence is not designed. It is a phase transition that occurs when scale crosses a certain threshold.

Just as water changes state from liquid to gas when temperature crosses a boundary, neural networks change cognitive state when their representational capacity becomes high enough to encode relationships that were previously inaccessible.

This is why:

a small Transformer cannot reason

a medium Transformer can reason inconsistently

a large Transformer can reason reliably (within bounds)

an enormous Transformer begins to exhibit meta-reasoning

The architecture doesn’t change.

The optimizer doesn’t change.

The training algorithm doesn’t change.

Only the scale changes… and suddenly the system behaves differently.

If you have ever trained progressively larger models on the same dataset, you’ve watched this happen.

There is no single point of emergence; instead, there is a gradient of capabilities that becomes unmistakably sharp beyond a certain compute frontier.

6.2. Emergence — When More Becomes Different

Emergence is the phenomenon where quantitative increases produce qualitative changes.

In neural networks, emergence is:

analogical reasoning

symbolic manipulation

multi-step planning

abstraction

self-correction

tool selection

aligned refusal behavior

long-horizon consistency

meta-cognition-like patterns

They arise because the model’s geometry becomes dense enough that high-level structure begins to self-organize.

Here’s my favourite analogy to make you understand this:

A small model is like fog: dispersed, disconnected, unstable.

A large model is like a crystal: structured, coherent, symmetrical.

Scaling is the freezing process that turns vapor into geometry.

This is why alignment succeeds more easily in large models.

It is not because larger models are inherently safer, they’re not…

But because their internal structure is smoother and more controllable.

In small models, alignment breaks because the geometry is chaotic.

In large models, alignment works because the geometry has “crystallized.”

But emergence brings both power and danger.

6.3. When Models Break: The Failure Modes of Scale

As models grow, new capabilities emerge — but so do new failure modes.

Here are the ones that matter most to builders:

1. Hallucination Through Overgeneralization

Larger models infer relationships too aggressively because they have richer representational density. Smaller models hallucinate due to ignorance. Larger models hallucinate due to overconfidence.

2. Reasoning Drift at Long Context Lengths

Long context windows introduce:

dilution

memory interference

context mixing

gradient instability

The model begins to lose track of earlier reasoning or subtly reinterpret its own premises.

You see this especially in models that exceed 50k+ tokens of context.

3. Fragility to Adversarial Prompts

With scale comes expressiveness and with expressiveness comes vulnerability.

Users can: jailbreak, roleplay, misdirect, bias, override the safety layer, etc.

Because the model’s verbal fluency becomes a liability.

4. Training Data Echoes

Larger models memorize more patterns, which means:

distributional artifacts leak into outputs

subtle biases amplify

rare events become exaggerated

stylistic fingerprints of datasets reappear

copyrighted or personal content may surface under edge conditions

This is not malicious.

It is the physics of overparameterized systems.

5. Misalignment Through Optimization Pressure

When you scale alignment processes improperly, the model becomes:

overly cautious

overly polite

overly restrictive

overly verbose

overly normative

This happens because reward models often overfit to specific adversarial datasets.

Alignment is an optimization problem.

And every optimization has a failure surface.

6.4. Alignment — What It Really Is

Most people think alignment means:

“making the model safe”

“preventing harmful outputs”

“following instructions politely”

But alignment is far deeper:

Alignment is the engineering discipline of shaping model behavior to match human values, objectives, constraints, and expectations… under uncertainty and adversarial conditions.

It is not one technique; it is a stack:

Pretraining data curation → shaping the model’s worldview

Supervised finetuning → teaching correct patterns of behavior

Preference modeling → learning what humans want

Reinforcement learning → sculpting behavioral tendencies

Evaluation systems → testing failure conditions

Guardrails → providing hard limits

Policy and safety layers → ensuring compliance

Monitoring → detecting drift and anomalies

Alignment is not something you “add” to a model.

It is something you continuously negotiate with it.

And the larger the model, the more subtle the negotiation becomes.

Alignment Is About Shaping Energy Landscapes

Under the hood, alignment is not a moral process.

It is not philosophical. It is not political.

It is geometric.

Neural networks carve out energy landscapes — vast multidimensional spaces where certain outputs are more “likely” than others.

Alignment shifts the shape of this landscape:

creating attractors for safe behavior

creating repellers for harmful behavior

modifying gradients to bias reasoning

introducing “traffic lanes” in output space

erecting conceptual guardrails

You do not teach a model to refuse dangerous content.

You shift the energy landscape such that refusal is the lowest-energy path.

This is both elegant and unsettling, because it means that:

alignment is statistical

alignment is never perfect

alignment depends on data, not commandments

alignment shifts when the world shifts

alignment is fragile

You are shaping a fluid, not programming a rule.

Why Larger Models Are Easier to Align (The Counterintuitive Truth)

In smaller models:

reasoning is inconsistent

geometry is noisy

behaviors are brittle

contradictions abound

Trying to align a small model is like trying to teach philosophy to fog.

But in larger models:

reasoning stabilizes

contradictions reduce

representations smooth out

latent structures organize themselves

Aligning a large model is like shaping a crystal lattice.

Small nudges propagate cleanly and predictably.

This is why:

GPT-4 is safer than GPT-3

Claude 3 Opus is safer than Claude 2

Llama 3 405B will align more easily than 70B

Scale does not guarantee safety… but it guarantees malleability.

The True Hard Problem: Not Alignment, But Post-Deployment Drift

Alignment works in the lab.

Drift happens in the real world.

As users push models to new domains, the model encounters:

adversarial prompting

creative misuse

domain shifts

edge-case reasoning

out-of-distribution tasks

It begins to: bend, stretch, re-anchor its internal representations, weaken its refusal criteria, and blur boundaries between safe and unsafe domains.

This is why monitoring is not an optional add-on.

It is the backbone of AI governance.

You do not deploy a model; you steward it.

6.5. The Philosophical Core: Intelligence, Control & the Limits of Scale

As models grow, something strange happens, they begin to:

interpret intent

infer hidden structure

resist certain prompts

choose better strategies

display self-correction

These behaviors look like agency.

But they are by-products of scaling and optimization.

A large model is not a mind.

It is a compression engine whose latent geometry has become so rich that human-like patterns begin to emerge.

This leads to a final uncomfortable truth:

Scale creates the illusion of mind, but not the presence of one.

Yet the illusion behaves powerfully enough that we must design as if it were real.

This is the paradox the next decade must face:

intelligence without understanding

agency without intent

reasoning without consciousness

alignment without guarantees

autonomy without identity

We are building systems that exhibit the behaviors of minds, without the ontology of minds.

Chapter 7 — Architecting AI Products: Systems, Pipelines, Constraints & Real-World Deployment

By the time you reach this point in the AI builder’s journey, you discover something that surprises almost everyone on the outside: the difficult part of building AI products is almost never the model itself.

Models are predictable. Models are well-behaved. Models are static artifacts of pretraining and fine-tuning that behave consistently under known conditions.

The world, however, is not predictable.

Users are not predictable.

Inputs are not predictable.

Constraints are not predictable.

Contexts are not predictable.

And the moment you put a model into production, you realize that AI product development is less about “AI” and more about engineering ecosystems around AI that can tolerate unpredictability without collapsing.

A model does not solve a problem.

A model in a system solves a problem.

And systems require architecture.

So let’s explore the architecture.

7.1. The First Principle of AI Product Design: A Model Is Not a Product

A model is:

a probability distribution

over sequences or representations

conditioned on inputs

learned from data

optimized for loss minimization

A product is:

a set of user experiences

delivered reliably

under constraints

with predictable outcomes

aligned with business goals

The distance between the two is enormous.

When a PM or founder tries to deploy a raw model directly into a UX, they discover almost immediately that models are: inconsistent and unpredictable at edge cases.

This is not a failure of AI.

This is the nature of stochastic systems.

So the role of the product builder is to wrap stochasticity inside deterministic structure.

This is the heart of AI product architecture.

7.2. The AI System Stack — The 8 Layers Every Working AI Product Must Have

A functioning AI product is built from eight interacting layers:

Input Sanitation Layer

Representation & Retrieval Layer

Model Invocation Layer

Reasoning & Orchestration Layer

Constraint & Safety Layer

Memory & Personalization Layer

Feedback & Evaluation Layer

Monitoring & Drift Detection Layer

Each layer exists because something in the real world will break without it.

Let’s go through them in the order they appear in real systems.

7.2.1. Input Sanitation — The Layer Almost Everyone Underestimates

Raw user input is chaos.

Users send:

malformed JSON

ambiguous questions

contradictory instructions

broken code

irrelevant context

harmful prompts

overly long text

empty text

multilingual fragments

half-sentences

sensitive information

adversarial tokens

If you feed raw input into an LLM, you will get raw output.

And raw output is unpredictable.

So the first task of any AI system is to construct a controlled input representation, using: format detection, PII filtering, truncation rules, schema alignment, etc.

You cannot build reliable outputs unless you first build reliable inputs.

This layer is the single most important predictor of downstream product stability.

7.2.2. Retrieval & Representation — Giving the Model the World It Needs

A model cannot use knowledge it does not have.

And it cannot hallucinate reliably enough to behave like it knows something.

So the second layer in any AI system is retrieval — the process of grounding the model in:

current data

personalized attributes

domain-specific knowledge

private corpora

historical state

up-to-date facts

Retrieval is not just about adding context.

It is about rewriting the model’s probability landscape by constraining it to operate within a factual bubble.

Tools include:

vector search

hybrid sparse + dense retrieval

multi-hop retrieval

context ranking

prompt compression

semantic filtering

relevance scoring

document chunking heuristics

The difference between an AI system and an AI toy is almost always the quality of the retrieval layer.

7.2.3. The Model Invocation Layer — Choosing the Right Model for the Right Purpose

This layer is deceptively simple: “Just call a model.”

But models differ dramatically in:

latency

cost

context length

hallucination tendencies

strength at reasoning

strength at summarization

strength at instruction-following

strength at creativity

safety behavior

A production-grade AI product rarely relies on a single model.

Instead, it uses a model router that selects the right model for the right task based on:

input complexity

user tier

latency budget

token count

required creativity

risk level

grounding requirement

cost-performance profiles

This is where you architect:

cascading LLM calls

fallback models

lightweight classifiers

safety checkers

fact-verification models

embedding-only paths

Think of model invocation as CPU scheduling for intelligence: you don’t run every process on the same core.

7.2.4. Reasoning Orchestration — Turning the Model Into a Thinker, Not a Text Printer

Raw LLM calls produce text, not solutions.

To obtain solutions, you need orchestration, which includes:

1. Chain-of-thought prompting to improve reasoning and self-consistency.

2. Tool calling to push model behavior beyond text generation.

3. Program-aided logic (PAL) to let the model generate code that solves the problem.

4. Verification loops to check correctness before returning answers.

5. Multi-agent decomposition where multiple specialized agents collaborate.

6. Self-reflection and self-correction where the model evaluates its own output.

7. Planning frameworks that let the model decide how to solve a task before it attempts solving it.

This layer converts generative prediction into structured cognition.

It is the difference between a model that outputs something plausible and a system that solves the actual problem.

7.2.5. Constraint & Safety Layers — Keeping the System Inside a Controlled Envelope

This is where real-world AI systems diverge from research prototypes.

Your product must:

avoid harmful content

avoid illegal responses

avoid toxic outputs

enforce business rules

prevent irreversible actions

avoid hallucinated APIs

avoid unsafe tool calls

enforce rate limits

comply with regulations

You do this not with a single safety layer but with multiple overlapping safety systems, including:

input classifiers

safety-specific LLMs

refusal templates

constrained decoding

guardrail grammars

restricted tool schemas

permissions checks

red-team prompts

automated adversarial testing

Large models are powerful.

But their power makes them unstable without constraints.

A good AI system is like a chemical reactor — the reactions are powerful, but the container must be engineered for pressure.

7.2.6. Memory & Personalization — Giving the System a Sense of Identity and Continuity

Users expect AI systems to remember:

prior tasks

long-term preferences

style

domain knowledge

organizational norms

previous mistakes

ongoing projects

But naive memory systems create:

hallucinated memories

privacy breaches

confusion between users

stale or contradictory state

retrieval overload

So memory must be:

structured

permissioned

versioned

selective

queryable

decayed over time

validated before use

The best AI products will have adaptive memory — which updates itself only when the update improves future predictions.

Memory is where personalization transforms from a gimmick into intelligence.

7.2.7. Feedback & Evaluation — The Layer That Turns Products Into Evolving Systems

An AI system that does not evaluate itself degrades over time.

Evaluation is not one process; it is many:

human preference collection

automatic scoring

regression testing

correctness evaluation

reasoning quality metrics

hallucination detection

latency monitoring

cost-performance tracking

You cannot improve what you cannot measure.

The best AI products have internal dashboards where developers can see: every prompt, failure, correction, etc.

This is where alignment continues after deployment.

7.2.8. Monitoring & Drift Detection — Keeping the System Stable as the World Changes

Even if your model is perfect the day you deploy it:

user behavior changes

input distributions shift

new adversarial patterns appear

your internal knowledge base evolves

your customers’ needs transform

regulations update

safety norms shift

Without drift detection, your system becomes silently misaligned.

You need:

anomaly detectors

retraining pipelines

versioned updates

user behavior analytics

distribution-shift alarms

automated rollback systems

A great AI product is not a static release.

It is a continuously adapting organism.

7.2.9.“LLMs Are Unreliable Alone, but Unstoppable in Systems.”

One of the most liberating realizations in AI product design is that you stop trying to make the model perfect and instead focus on making the system resilient.

You accept that:

the model will hallucinate

the model will misinterpret inputs

the model will reason incorrectly

the model will forget

the model will mis-handle formats

the model will contradict itself

But you design a system in which these failures are:

caught

corrected

neutralized

or made irrelevant

This is why system architecture is the real differentiator.

Two companies using the same model can produce entirely different product experiences — one polished, reliable, enterprise-grade; the other chaotic, brittle, amateurish.

The difference is the system, not the model.

CHAPTER 8 — The New AI Product Manager: Skills, Mindsets, Mistakes & the Career Landscape of the AI Era

You have now absorbed how models learn, how they reason, how they imagine, how they fail, how they scale, how they behave, and how they are encased inside production systems.

Now, what does it mean to be a product manager in the age of AI?

And even deeper: What does a product manager need to become to stay relevant in a world where intelligence itself is a building block?

The truth is both liberating and uncomfortable:

AI does not merely change the tools PMs use, it changes what PMs are.

Traditional PMs optimized workflows, coordinated teams, managed roadmaps, and wrote PRDs that translated customer needs into software behaviors.

But AI PMs operate in a world where software is no longer deterministic, where systems behave probabilistically, where user experience changes depending on context, where outputs are not “designed” but discovered.

Where behavior emerges from geometry rather than code, where correctness is sometimes approximate rather than absolute, and where influence comes not from perfect plans but from orchestrating complex systems under uncertainty.

In this world, the PM role expands, dissolves, reshapes, and reforms into something deeper: a hybrid between product strategist, probabilistic thinker, AI architect, behavioral economist, constraints engineer, data curator, and system philosopher.

Let’s unpack what that means — slowly, thoroughly, and honestly.

8.1. The First Shift: From Feature Thinking to System Thinking

Traditional product management encourages thinking in features: buttons, flows, screens, APIs, modules — discrete units of capability that produce predictable outcomes, because deterministic software behaves like a machine with gears, levers, and switches.

AI systems do not work like this.

An AI feature is not a gear; it is a probabilistic field of behavior shaped by: prompts, models, retrieval results, safety layers, user inputs, etc.

Therefore, the modern PM must think not in terms of “what the system does,” but “how the system behaves under a wide distribution of possible interactions.”

This requires a shift from designing surfaces to designing ecosystems, from designing flows to designing constraints, from designing screens to designing feedback loops, and from designing specific functionalities to shaping latent behavioral spaces.

This is not optional.

It is simply how AI works.

8.2. The Second Shift: From Requirements to Probabilities

The old PM universe was binary — requirements were met or not met, acceptance criteria passed or failed, features shipped or didn’t ship. A PM could define success with crisp logic statements.

AI PMs live in gradients.

No AI system is:

fully correct,

fully safe,

fully consistent,

fully predictable.

Instead, everything is expressed in probabilities:

“The hallucination rate must stay below X%.”

“The system should degrade gracefully under Y conditions.”

“Similarity scores must remain above Z thresholds.”

“Safety failures must drop by N standard deviations after alignment tuning.”

“The grounding pipeline should reduce uncertainty in long-context reasoning.”

This means the AI PM must learn to reason fluently about distributions, error surfaces, uncertainty budgets, and trade-offs that have no binary answer but require calibrated judgment.

This is why the best AI PMs sound more like economists or physicists than classical software managers — they speak in likelihoods, trade-offs, expected values, and boundary conditions.

8.3. The Third Shift: The PM Becomes a Curator of Data, Not Just a Writer of PRDs

In deterministic software, the artifact that matters is code.

In AI systems, the artifact that matters is data — the prompts, examples, demonstrations, documents, embeddings, schemas, and instruction datasets that shape the model’s behavior.

A single poorly curated document can distort an entire product experience.