The AI Product Pricing Masterclass: OpenAI Product Lead on Why SaaS Pricing Fails in AI (and How to Fix It)

If you think pricing AI products is about tokens, you’re already behind. This deep dive exposes the hidden economics of AI and how PMs can design pricing that survives real-world usage.

In traditional SaaS, the system’s behavior is deterministic. You click a button, the same logic runs every time. Costs also behave nicely: once you amortize infrastructure, the marginal cost of serving one more user trends toward zero.

Pricing models grew up around that reality. Seats, tiers, bundles, “unlimited” plans. The core assumption was simple: more usage is good, because costs flatten as you scale.

AI flips that assumption.

In AI systems, the product does not just execute code. It reasons. And reasoning is not free. It is variable, sometimes unpredictable, and often unbounded unless you explicitly design it to be.

Every interaction triggers a cascade of costs that depend not just on how many users you have, but on how they behave, what they ask, how often they retry, how complex their workflows become, and how much parallel demand they create.

This is why AI pricing is not an extension of SaaS pricing. It is a different discipline altogether.

In this post, we discuss:

Why AI Product Pricing Is Fundamentally Different From SaaS

The Real Cost Structure of AI (The 7 Layers)

The Four AI Pricing Models (and When to Use Each)

Stability vs Scale: The Strategic Tension

How to Choose Your AI Pricing Model: A Decision Tree

AI P&L: A Full Unit Economics Breakdown

Conclusion

AI Cost Glossary

Let’s dive in.

1. Why AI Product Pricing Is Fundamentally Different From SaaS

1.1 The death of “zero marginal cost” thinking

The most dangerous SaaS habit AI teams carry forward is the belief that marginal cost eventually disappears. In AI, it never does.

Every meaningful AI interaction has a real cost attached to it: not just tokens, but compute allocation, latency trade-offs, orchestration overhead, retrieval, and often retries or fallback paths.

There is no finish line where you’ve “paid the cost once” and can now scale freely.

Even worse, the marginal cost isn’t stable. It changes as your product evolves, as users get more sophisticated, and as edge cases accumulate.

The same feature that was cheap at launch can become expensive six months later simply because users learned how to push it harder.

In SaaS, growth tends to smooth costs. In AI, growth often amplifies them.

This is the first mental shift pricing must reflect: your AI system remains economically alive forever.

1.2 Costs scale with behavior, not just users

In SaaS, two customers on the same plan usually cost roughly the same to serve. In AI, two customers paying the same amount can have radically different cost profiles.

One user might ask short, well-scoped questions, accept imperfect answers, and move on. Another might run long, iterative workflows, repeatedly refine prompts, trigger multiple retries, and expect high accuracy every time.

From a pricing perspective, these two users look identical. From a P&L perspective, they are opposites.

This is what makes AI pricing unintuitive. The thing you celebrate (engagement) is often the thing that destroys margins if it isn’t constrained or monetized properly.

Traditional pricing assumes usage correlates with value. AI breaks that assumption.

Usage correlates with cost volatility, not guaranteed value. Some of the most expensive interactions are exploratory, redundant, or compensating for system weaknesses rather than delivering incremental benefit.

That means pricing can no longer be passive. It has to shape behavior.

If your pricing doesn’t influence how users interact with the system, the system will eventually influence your margins instead.

1.3 Variance is the real enemy

Most teams obsess over average cost per request. That’s the wrong metric.

AI systems don’t fail on averages. They fail when real usage creates variance.

Variance shows up everywhere: prompt length, context size, retries, parallel usage spikes, long-tail edge cases that require heavier models, and moments where the system has to work much harder to maintain quality.

SaaS pricing models assume variance is negligible. AI pricing models must assume variance is inevitable.

The uncomfortable implication: pricing must be designed for worst-case behavior, not typical behavior. If your pricing only works when users behave “nicely,” it doesn’t work.

This is why many AI products look profitable in early metrics and then fall apart as usage deepens. Early users are forgiving and exploratory. Later users are demanding and efficient at extracting value which usually means extracting cost.

1.4 AI pricing is a system control mechanism

Here’s a framing most teams miss: pricing in AI is not just a way to charge money. It is one of the strongest control mechanisms you have.

Pricing determines:

how often you invoke reasoning

how much you experiment

whether you batch work or stream it

whether you tolerate latency

whether you retry aggressively

whether you push the system to edge cases

In SaaS, pricing mostly controls access. In AI products, pricing controls behavioral pressure on the system.

If pricing encourages unbounded exploration without cost feedback, you will push the system until it breaks.

If pricing is too restrictive too early, you will never discover value.

Great AI pricing doesn’t just extract revenue. It teaches you how to use the product in a way the system can sustainably support.

1.5 Why “fair” pricing is a trap

A lot of early AI products aim for fairness: flat plans, simple tiers, “unlimited” usage with soft limits. It feels user-friendly, and in the short term it often boosts adoption.

But fairness is not the goal. Survivability is.

AI pricing that feels fair but ignores variance transfers all risk to the company while giving you no incentive to behave efficiently.

Over time, the system absorbs more stress until engineering adds silent limits, quality degrades, or finance forces abrupt pricing changes that anger customers.

The irony: “unfair” pricing that reflects real costs and constraints often builds more trust in the long run.

You can tolerate explicit limits. What you hate is inconsistency: unpredictable throttling, sudden downgrades, or quiet degradation.

Honest pricing aligned with system reality beats generous pricing that lies.

1.6 The PM role changes here

This is where the AI PM role diverges from traditional product management.

In SaaS, PMs could largely ignore pricing mechanics once tiers were set. In AI, PMs cannot. Pricing decisions influence architecture, and architectural decisions influence pricing viability. You cannot separate the two.

An AI PM must understand:

which user actions are expensive

which costs are fixed vs variable

which behaviors create cascading load

which quality improvements are linear vs exponential in cost

Without this, PMs accidentally design features that are economically incompatible with the pricing model.

The product looks great, usage climbs, and finance quietly panics.

AI pricing failure is rarely one bad decision. It’s a slow accumulation of small misalignments between system behavior, user behavior, and pricing assumptions.

1.7 The core AI pricing mistake, stated plainly

The most common mistake teams make is pricing AI as if cost is something to optimize later.

In AI, pricing is system design, not a go-to-market tweak.

It decides who absorbs variance and which behaviors your system must constrain under real user pressure.

If you don’t design pricing with the same rigor as system architecture, the system will expose that weakness at scale. Not immediately. Not loudly. But inevitably.

SaaS taught us to chase growth first and fix economics later. AI punishes that mindset.

Growth without pricing discipline is not momentum. It’s deferred failure.

Everything builds on this foundation: AI pricing is different because AI systems never stop costing money, never behave predictably, and never forgive lazy assumptions.

If you accept that early, pricing becomes a strategic weapon. If you don’t, it becomes the reason your product dies quietly while “everything looked fine.”

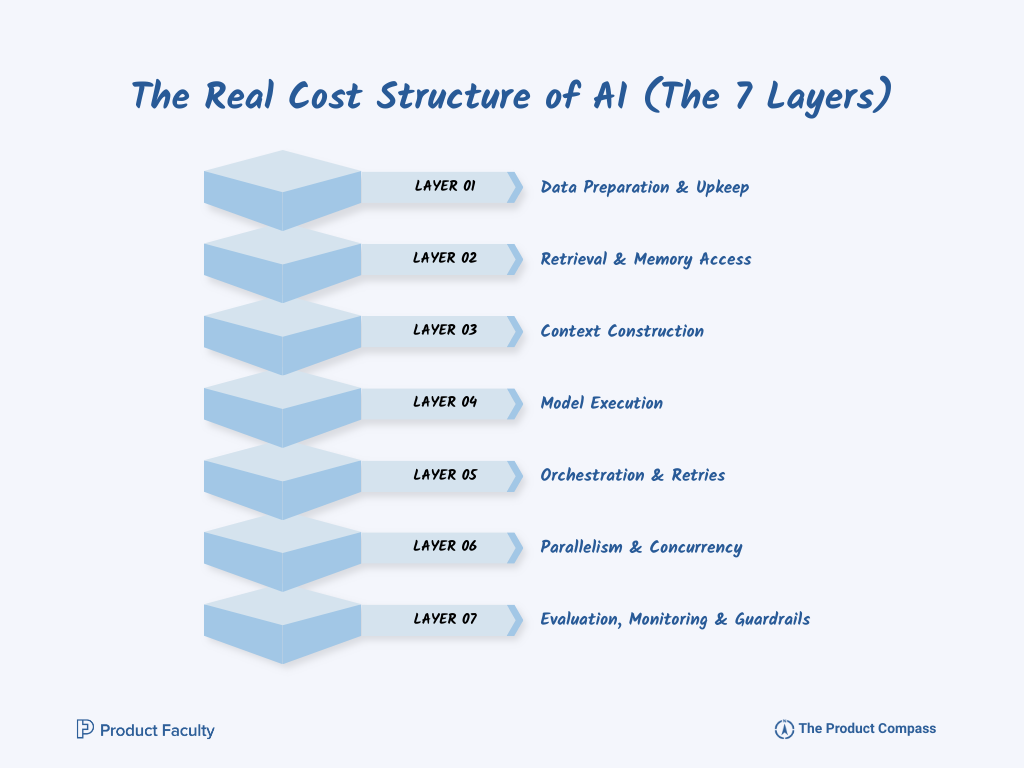

2. The Real Cost Structure of AI (The 7 Layers)

If you ask most teams where their AI costs come from, they’ll say “tokens.”

That answer is understandable, visible, and dangerously incomplete.

Tokens are the easiest cost to see because they show up cleanly on invoices, dashboards, and alerts. But in real AI systems, tokens are rarely what kills you.

What kills you is everything around them: the quiet layers that compound, interact, and magnify each other until your unit economics collapse while your token graphs still look “reasonable.”

To price AI correctly, you have to understand its true cost structure not as a single line item, but as a layered system where inefficiencies stack.

I’ve found the most accurate way to think about AI cost is as seven layers, each one capable of quietly multiplying the next.

2.1 Layer 1: Data preparation and upkeep

This is where most teams underestimate cost before they even ship.

AI products don’t run on “data” in the abstract. They run on data that has been cleaned, structured, embedded, versioned, and kept up to date.

Every document you ingest eventually needs reprocessing. Every schema you introduce creates maintenance overhead. Every shortcut you take early turns into recurring cost later.

This cost doesn’t care about usage. It cares about scope.

And because it isn’t directly tied to queries, it’s often excluded from pricing discussions, even though it belongs in your COGS model.

If your pricing doesn’t account for the fact that knowledge must be continuously refreshed and reshaped, you are subsidizing every future feature you add.

2.2 Layer 2: Retrieval and memory access

Retrieval is often introduced as a quality improvement, not a cost driver. That’s why it’s frequently mispriced.

Every retrieval operation has a cost: vector searches, ranking, filtering, post-processing, and latency overhead.

But the real cost isn’t the retrieval call itself. It’s what happens when retrieval is sloppy.

Poor retrieval design pulls too much information “just in case.” That extra context flows downstream into the model, inflating context length, increasing inference cost, and slowing responses.

In other words, retrieval mistakes don’t just cost money once. They amplify cost everywhere else.

Teams justify this with “better safe than sorry.” Economically, that mindset is disastrous.

Pricing models that don’t account for retrieval discipline reward inefficiency. You don’t see the cost, so you trigger workflows that retrieve far more than you need.

The system absorbs it until it can’t.

2.3 Layer 3: Context construction

Context is where AI systems quietly bleed money.

Every extra paragraph added to context increases cost, latency, and variance. Context growth is subtle. A small instruction added here. A clarification added there. A “just in case” rule appended after an incident. None of these decisions feel expensive in isolation.

Six months later, you have a bloated prompt that costs five times what it did at launch, and nobody remembers why.

From a pricing perspective, this is critical: context is one of the cost drivers you directly control, yet it’s rarely treated as an economic decision.

Pricing that ignores context growth assumes the system will never evolve.

It always does.

2.4 Layer 4: Model execution

This is the layer everyone fixates on, and for good reason. Models are expensive, and choosing the wrong one at the wrong time can wipe out margins.

But the real mistake isn’t using large models. It’s using them by default.

In production systems, the correct model choice is almost never static. Some tasks require deep reasoning. Others require speed. Others require consistency.

Routing everything through the “best” model is a convenience decision disguised as a quality decision.

The economic cost of this laziness shows up slowly. Margins thin. Finance asks why. Engineering points to user demand. PMs argue quality. Everyone is technically correct, and the system still loses money.

Pricing that assumes a single model cost is fantasy pricing. Real AI pricing must assume dynamic routing, and it must be resilient to mistakes in that routing.

2.5 Layer 5: Orchestration and retries

Modern AI products are not single calls. They are workflows.

A single user action might trigger a planner, a worker, a validator, a formatter, and a fallback path if confidence is low. Each of these steps may call a model. Some may retry automatically. Others may escalate to a heavier model.

None of this is visible to you, which makes it easy to forget it exists when pricing.

But orchestration is where AI costs multiply silently. One user request becomes five or ten model calls. A single retry doubles cost instantly. A safety check adds latency and compute but no visible feature.

These costs are the result of good intentions: reliability, safety, quality. That’s why teams hesitate to price for them explicitly. But ignoring them doesn’t make them free. It just hides them until margins collapse.

Pricing that doesn’t fund orchestration complexity is effectively betting that reliability won’t matter.

It always does.

2.6 Layer 6: Parallelism and concurrency

If there is one layer that kills otherwise healthy AI businesses, it’s this one.

Parallelism is not about how many total requests you handle. It’s about how many you handle at the same time.

Ten users spread across an hour are cheap. Ten users hitting the system in the same second are expensive.

They force you to provision capacity for peak load, not average behavior. That capacity costs money whether it’s used or not.

This is why AI systems feel fine in testing and fall apart under success.

Early usage is staggered and forgiving. Real adoption is spiky, synchronized, and merciless.

Pricing that doesn’t account for concurrency implicitly promises infinite capacity. The system cannot deliver that promise without burning cash.

Capacity-aware pricing is not an enterprise luxury. It’s a survival mechanism.

2.7 Layer 7: Evaluation, monitoring, and guardrails

The final layer is the one serious teams can’t avoid.

If your AI system matters, you will pay to monitor it. If it touches money, decisions, customers, or risk, you will log outputs, evaluate quality, audit failures, and add guardrails.

These costs scale with importance, not usage. The more people rely on the system, the more you invest here. And unlike tokens, these costs don’t shrink when usage drops. They are structural.

Pricing models that pretend evaluation is “overhead” are lying to themselves. If your product requires trust, trust must be priced in.

2.8 Why these layers compound, not add

The most important thing to understand about the seven layers is that they interact.

A retrieval inefficiency inflates context. Inflated context increases inference cost. Higher inference cost encourages routing to smaller models, which increases error rates. Errors trigger retries. Retries increase concurrency pressure. Concurrency pressure forces overprovisioning. Overprovisioning raises baseline cost.

This is how AI costs spiral without any single decision looking “wrong.”

And this is why pricing must be conservative by design. You are not pricing a stable machine. You are pricing a living system that accumulates complexity over time.

2.9 What this means for pricing decisions

Once you see the full cost stack, one thing becomes clear: pricing must absorb uncertainty.

You cannot price AI assuming perfect efficiency, perfect routing, perfect retrieval, and perfect behavior. You must price assuming drift, mistakes, and growth in complexity.

The teams that survive are not the ones with the lowest per-token cost. They are the ones whose pricing models are resilient to the system getting messier over time.

If your pricing only works when everything goes right, it doesn’t work.

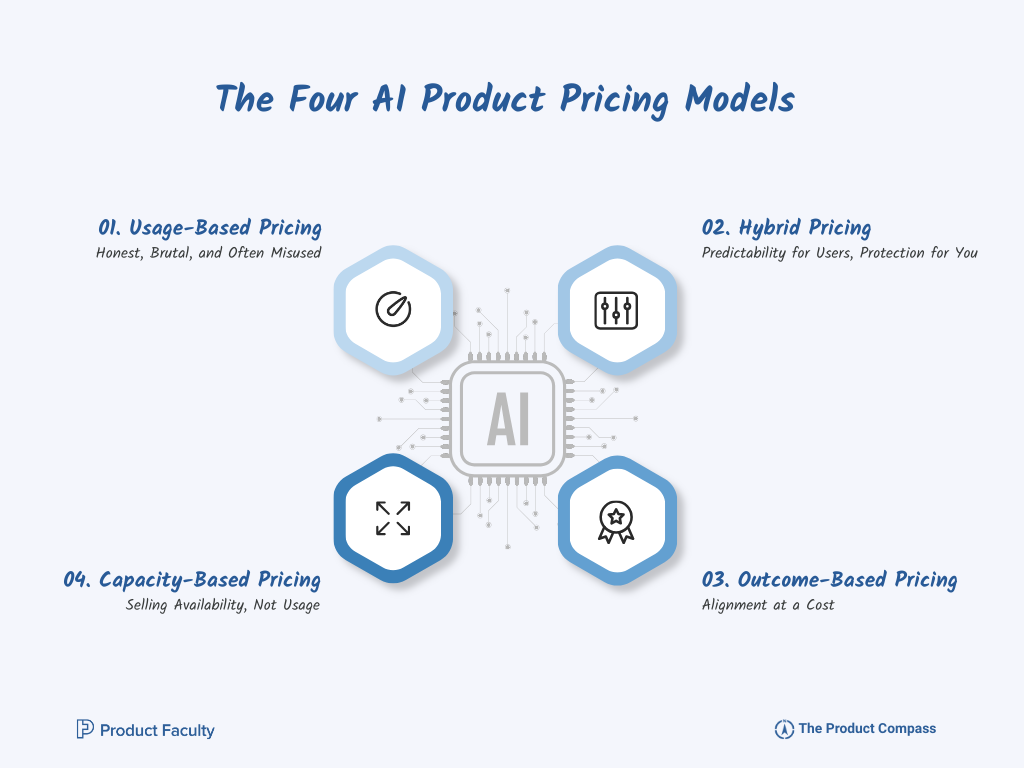

3. The Four AI Product Pricing Models (and When to Use Each)

Once you accept AI pricing can’t be treated like SaaS pricing, the next mistake is over-engineering the solution.

Teams invent exotic hybrids, clever credit systems, abstract “AI units,” or opaque bundles that look smart on a slide but collapse the moment real users touch the product.

In practice, AI products converge to four pricing models that survive real usage.

What matters is not creativity. What matters is whether the pricing model maps cleanly to how cost is generated inside your system, and whether it nudges users toward behavior your system can afford.

3.1 Usage-based pricing: honest, brutal, and often misused

Usage-based pricing is the most straightforward model: users pay for what they consume. Tokens, queries, compute units, requests… pick your unit.

This model feels “right” to engineers and finance teams because it aligns cleanly with marginal cost. Every extra unit of usage produces revenue. Every spike in cost is theoretically covered.

The problem is that users are not economists.

In practice, usage pricing introduces something that kills many AI products before they reach maturity: meter anxiety. The moment users feel like every interaction is ticking a meter, they subconsciously pull back. They stop experimenting. They avoid edge cases. They use the product less precisely when they should be discovering where the value actually lies.

This is why usage pricing works best in environments where users already expect it. Developer tools. APIs. Infrastructure. Places where buyers think in throughput, budgets, and efficiency. In those contexts, usage pricing is not scary; it’s familiar.

But when teams apply usage pricing to productivity tools, consumer products, or exploratory workflows, adoption stalls. Users don’t want to think about cost while they’re still learning what the product can do.

There’s another subtle risk: usage pricing assumes users can control cost drivers. In AI systems, they often can’t. A user might submit the same request twice and get two radically different internal cost profiles because one path triggered retries or heavier models.

From the user’s perspective, that feels unfair, even if it’s economically justified.

Usage pricing works when:

you understand what drives cost

the system behaves predictably

you are comfortable optimizing usage

If any of those fail, usage pricing becomes a growth ceiling, not a revenue lever.

Example: OpenAI API

OpenAI prices its API based on input and output tokens. The more tokens you send and receive, the more you pay. This is the clearest and most widely accepted example of usage-based pricing in AI. Nearly every major AI API provider follows this same principle.

3.2 Hybrid pricing: predictability for you, protection for the business

Hybrid pricing exists because pure usage pricing is too harsh for most real-world products.

In a hybrid model, users pay a base subscription that includes a reasonable amount of usage, with overages kicking in once they exceed that baseline. Psychologically, this creates safety. Economically, it creates a buffer.

This is the most common and most misunderstood AI pricing model.

The strength of hybrid pricing is that it decouples exploration from punishment. Users can play, learn, and build habits without watching a meter, while the business retains the ability to capture revenue from heavy or expensive usage.

But hybrid pricing fails when teams treat it as a generosity exercise instead of a control system.

The included usage must reflect what the system can handle sustainably for the median user, not what looks attractive on a pricing page. Over-including usage trains users to behave expensively, and once that behavior is learned, clawing it back is painful.

Another common mistake is hiding overage mechanics. Teams worry that showing overage pricing will scare users, so they bury it or avoid it altogether. This backfires later when costs spike and pricing has to change abruptly.

Done well, hybrid pricing creates a quiet but powerful dynamic: most users stay comfortably within the base tier, while a minority of heavy users fund the variance for everyone else. Done poorly, it subsidizes your most expensive customers indefinitely.

Hybrid pricing is ideal when:

users need freedom to explore

costs vary widely across users

you want predictable revenue without unlimited exposure

Example: Notion AI

Notion AI is bundled into a subscription that includes a fixed allocation of AI credits. Once users exceed those credits, they must purchase additional credits or upgrade to a higher plan. This is a classic example of hybrid pricing — subscription first, usage second.

3.3 Outcome-based pricing: alignment at a cost

Outcome-based pricing is the model everyone talks about and few teams can sustain.

Instead of paying for usage, you pay for results: a ticket resolved, a lead qualified, a document processed correctly.

From your perspective, this is perfect. You don’t care how the AI works. You care if it delivers value.

From a system perspective, it is unforgiving.

Outcome pricing only works if teams can:

define outcomes unambiguously

measure them reliably

deliver consistently

absorb failures without destroying margins

Most AI systems aren’t stable enough for this early. When outcomes are priced, every failure becomes a revenue problem.

This forces heavy investment in evaluation, monitoring, and often human-in-the-loop.

There’s also a psychological trap: when users only pay for success, they push the system harder. They retry more. They test boundaries. That behavior increases cost even when revenue stays flat.

Outcome pricing works best when:

the task is narrow and well-defined

the value of success is high

the system is mature enough that reliability is not a question

For early-stage AI products, outcome pricing is often aspirational. It becomes viable later, once reliability is no longer a question.

Example: Enterprise AI Automation & Copilot-Style Agents

In enterprise environments, companies (including Microsoft through its evolving Copilot strategy) are increasingly exploring pricing based on work performed by AI agents, rather than raw token usage. Satya shared this in a podcast with Dwarkesh.

This moves pricing closer to outcome-aligned models, where customers pay for completed tasks or delivered value.

3.4 Capacity-based pricing: selling availability, not usage

Capacity-based pricing is underused despite mapping well to how AI systems fail.

Instead of paying for how much you consume, you pay for how much capacity you reserve: concurrency limits, throughput guarantees, response-time SLAs, parallel workflows.

This model recognizes a truth: many AI costs are driven not by total volume, but by peak demand.

If ten customers hit the system at once, the business pays for that concurrency whether you use it continuously or not. Capacity pricing monetizes that reality.

From the customer’s perspective, this model makes sense in enterprise and mission-critical contexts. They don’t want “cheap.” They want reliable. They are willing to pay to know the system will respond when needed.

The challenge is that capacity pricing requires operational maturity. You must actually be able to enforce limits, manage queues, and honor guarantees. You can’t fake it.

Capacity pricing works best when:

latency matters

concurrency drives cost

you value reliability over raw usage

workloads are predictable in bursts

It is rarely the first pricing model a company adopts, but it is often the one that unlocks sustainable scale.

Example: GPU / AI Compute Marketplaces

Platforms like SF Compute allow organizations to buy or reserve compute capacity, such as GPU time, instead of paying per request. This reflects capacity-based pricing, where customers pay for guaranteed availability and peak throughput rather than average usage.

3.5 The real mistake: choosing based on fashion, not physics

What kills pricing strategies isn’t picking the “wrong” model. It’s picking a model that doesn’t match the physics of your system.

If costs spike with concurrency but pricing is purely usage-based, you lose money under success.

If costs vary wildly by task complexity but pricing is per seat, heavy users destroy margins.

If the system is unstable but pricing is per outcome, reliability costs overwhelm revenue.

Pricing models are economic constraints. They must reflect how your system behaves, not how you wish it behaved.

3.6 The rule you learn in postmortems

If your pricing model doesn’t get stricter as usage grows, your margins will get worse as success grows.

Every viable AI pricing model tightens constraints as demand increases. It charges more, limits capacity, enforces overages, or demands higher commitment.

If pricing only encourages more usage without increasing discipline, it isn’t pricing. It’s a subsidy that increases your problems.

Side Note: Pricing is system design. You can’t do it well without understanding how AI products actually work.

If you want to learn that end to end, here’s the program I recommend: AI Product Management Certification (with Miqdad Jaffer, Product Lead at OpenAI). I lead the AI Builds Lab and run 3 live sessions in the cohort.

Next cohort: January 27, 2026. $500 off for our community:

Continue Reading

Up to here, you’ve got the foundation for AI product pricing (3,800+ words):

why AI pricing is different from SaaS

the 7-layer cost stack (and why the layers compound)

the 4 pricing models that survive real usage

the rule you learn in postmortems

If you want the practical part, the rest (4,200+ words) goes deeper into:

stability vs scale, and how premium tiers are really “stability budgets”

a decision tree you can apply to your product

an AI P&L breakdown (including peak behavior and concurrency, even when you use APIs)

AI cost glossary

If this helped, forward sections 2 and 3 to your product and engineering leaders. It’s the fastest way to get aligned before you ship pricing.

4. Stability vs Scale: The Strategic Tension

Every AI product hits a wall: the system cannot be both perfectly stable and infinitely scalable at the same time, at a price customers will pay.

This isn’t a temporary limitation. It is a structural reality of AI systems.

Pricing is where that reality is either acknowledged or hidden until it explodes.

4.1 What stability means in AI

Stability in AI isn’t uptime. It’s about predictability of behavior.

A stable system:

gives consistent answers for similar inputs

fails gracefully instead of catastrophically

avoids hallucinations in high-stakes contexts

maintains quality under load

behaves within known bounds

Achieving stability is expensive. It requires heavier models, guardrails, validation steps, retries, fallback logic, and often human review. Every layer added to reduce variance adds cost, latency, or both.

Stability is not a switch. It is a budget you allocate continuously.

4.2 What scale means in AI

Scale is not just more users. It’s more simultaneous demand, more diverse use cases, and more edge-case pressure.

Scaling means:

handling bursts of parallel requests

supporting a wider range of tasks

accommodating different expectations

absorbing variability in input quality and intent

Scale rewards efficiency. Smaller models. Aggressive routing. Less context. Fewer retries. Tighter timeouts.

Everything that improves throughput (work per minute) tends to reduce stability.

This is where the tension becomes unavoidable.

You can make the system more stable by letting it think longer, check itself, and retry when uncertain. But that reduces throughput and increases cost.

Or you can make it scale by pushing work through quickly and cheaply. But quality becomes more probabilistic.

Pricing is how you decide which one you are selling.

There is no free lunch here. Anyone promising otherwise is selling a story, not a system.

4.3 The pricing illusion: promising both without paying for either

Many AI products promise stability and scale while pricing as if neither has a cost.

Marketing says enterprise-ready. Pricing assumes optimistic averages. Engineering adds safeguards to prevent disasters. Finance sees margins slipping. Nobody connects the dots publicly.

This is how trust erodes internally before it erodes externally.

Stability and scale are not features. They are economic choices. If pricing doesn’t encode those choices, the system absorbs the tension until something breaks — often quality first, then margins.

4.4 Why stability costs grow faster than you expect

One of the hardest lessons teams learn is that stability costs are not linear.

The first layer of guardrails is cheap. The second is manageable. The third introduces orchestration overhead. The fourth triggers retries. The fifth requires fallback models. By the time you’re “enterprise-ready,” the cost per request can be multiples of what it was at launch.

What’s worse is that these costs tend to grow precisely when usage grows, creating a compounding effect. The more people rely on the system, the more you invest to make it safe. The more you invest, the harder it becomes to serve everyone cheaply.

Pricing that doesn’t anticipate this forces reactive behavior: silent degradation, hidden limits, or sudden pricing changes that feel arbitrary.

4.5 Why scale punishes generosity

Generous pricing works when systems are forgiving. AI systems aren’t.

When pricing encourages unlimited or near-unlimited usage, you will push the system in ways the team never intended. You’ll chain workflows, run experiments in parallel, and rely on the AI for tasks it wasn’t optimized for.

From your perspective, that’s rational. From the system’s perspective, it’s a stress test.

Scale punishes generosity because generosity trains behavior. And once you learn that behavior, it’s almost impossible to unteach without backlash.

That’s why the best AI pricing models feel slightly restrictive. Not hostile. Just honest. They make limits explicit, and they make heavy usage come with consequences.

4.6 Premium tiers as “stability budgets”

One effective way to manage this tension is to separate stability from scale explicitly.

Premium tiers don’t just buy more usage. They buy:

lower variance

better models

more retries

stricter guarantees

priority capacity

This isn’t price discrimination. It’s aligning expectations with economics.

If every user expects enterprise-grade stability at consumer-grade pricing, the system can’t survive.

Someone has to pay for predictability.

4.7 The routing dilemma: stability vs efficiency in practice

This tension shows up most clearly in model routing decisions.

Suppose your system can route a request to a smaller, cheaper model that works 80% of the time, or a larger, more expensive model that works 98% of the time.

At low scale, teams default to the larger model. It keeps quality high and complaints low. At scale, that decision becomes unsustainable.

The right answer is not purely technical. It’s economic. And pricing must reflect that decision.

If pricing assumes high-cost routing but usage grows faster than expected, margins collapse. If pricing assumes cheap routing but users expect premium quality, trust collapses.

The only sustainable path is to tie routing decisions to pricing tiers, making the tradeoff explicit instead of hidden.

4.8 Why pretending the tension doesn’t exist is fatal

The most dangerous posture an AI team can take is denial.

Teams tell themselves:

“We’ll optimize later.”

“Model costs will come down.”

“Users won’t push it that hard.”

“We’ll figure it out once we have more data.”

Sometimes these things are partially true. But none of them remove the tension. They just delay it.

And when the tension finally surfaces, it does so under pressure: during a growth spike, an enterprise deal, or a public failure. That’s the worst possible moment to redesign pricing.

4.9 The teams that survive do one thing differently

The teams that survive long-term do something that feels uncomfortable early:

They price conservatively before they need to.

They assume variance will increase. They assume stability will cost more than planned. They assume scale will arrive in bursts, not smooth curves.

And they encode those assumptions into pricing from the start, even if it slows growth slightly.

That tradeoff is rarely celebrated. But it’s the difference between products that quietly compound and products that burn brightly and disappear.

4.10 The core lesson

Stability and scale are not engineering problems waiting to be solved. They are economic forces that must be balanced continuously.

Pricing is the mechanism that performs that balancing act.

If pricing ignores the tension, the system absorbs it.

If pricing acknowledges it, the system survives it.

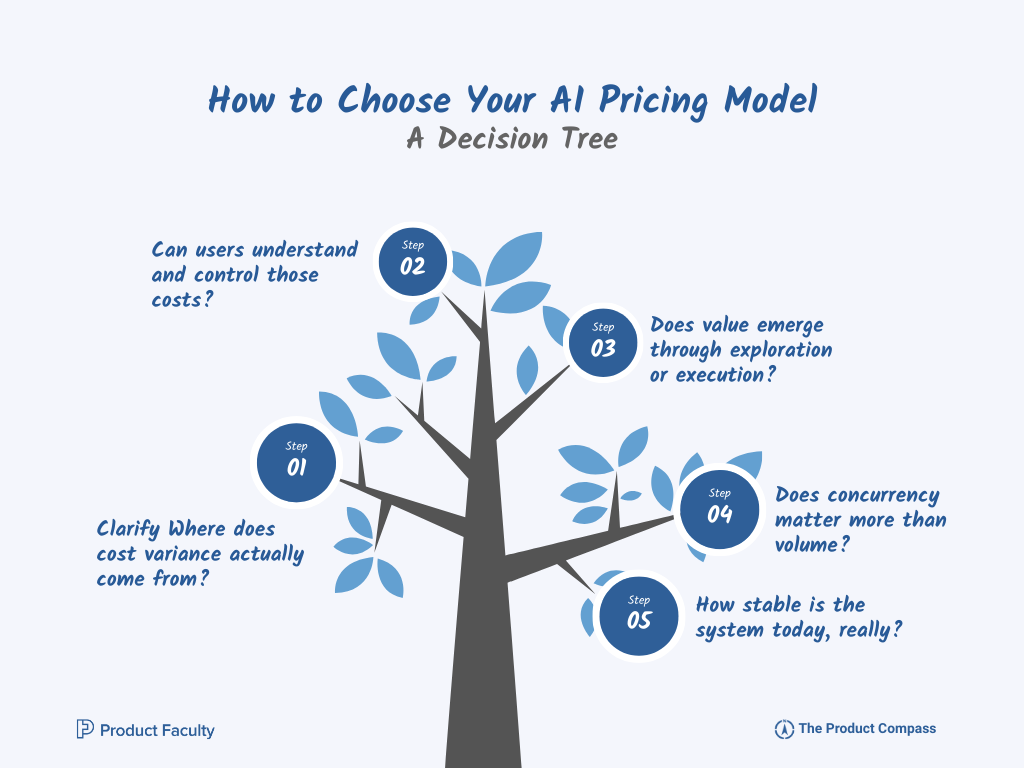

5. How to Choose Your AI Pricing Model: A Decision Tree

By the time teams reach this point, they’re usually asking the wrong question.

They ask, “Which pricing model is best?”

What they should be asking is, “Which pricing model survives the way our system actually behaves?”

AI pricing decisions fail not because teams lack options, but because they treat pricing as a competitive choice instead of a systems consequence.

They look outward, at what other companies are charging, what sounds simple, what sales teams prefer, rather than inward, at where cost variance is created, where the system breaks under pressure, and which behaviors need to be constrained.

The decision tree for AI pricing is not elegant. It’s uncomfortable. It forces you to confront realities about your product that teams often prefer to postpone.

Let’s walk through that decision tree the way an experienced AI PM would, starting not with pricing models, but with system truths.

5.1 Step 1: Where does cost variance actually come from?

This is the first fork, and the one most teams skip.

You must be able to answer, concretely, where your system’s costs explode. Not in theory. In practice.

For some products, cost variance comes from how often users invoke the system.

For others, it comes from how complex each invocation becomes.

In agentic systems, it often comes from how many steps a workflow triggers.

In real-time products, it comes from how many requests happen simultaneously.

If you can’t name the top two variance drivers with confidence, you are not ready to price the product.

This is why early pricing decisions are so dangerous. Before real usage data exists, teams guess. They assume average behavior. AI systems punish averages.

Pricing must target the tails.

5.2 Step 2: Can users understand and control those costs?

The next fork is psychological, not technical.

If users can clearly understand what drives cost and have agency to control it, usage-based pricing becomes viable. Developers, data teams, and infrastructure buyers live in this world. They are comfortable trading efficiency for savings.

If users cannot see or control cost drivers, which is true for most AI-powered workflows, usage pricing creates frustration. Users feel punished for behavior they don’t fully understand, and that erodes trust faster than almost anything else.

This is where hybrid pricing usually enters the picture. It shields users from complexity while still giving the business a release valve for extreme usage.

The mistake teams make here is assuming education solves everything. It doesn’t. Most users do not want to think about model routing, context length, or retries. Pricing must respect that cognitive reality.

5.3 Step 3: Does value emerge through exploration or execution?

This is a subtle but critical distinction.

Some AI products deliver value immediately, on the first successful outcome. Others only deliver value after users explore, experiment, and gradually build trust.

If value is immediate and measurable, outcome-based pricing can work, eventually. If value emerges through exploration, outcome pricing is premature and punitive.

Exploratory products require psychological safety. Users must feel free to try things, fail, and iterate without watching costs rack up. That almost always rules out pure usage or outcome pricing early on.

This is why so many early AI products start with hybrid pricing even if they plan to move toward outcomes later. The pricing must match the product’s learning curve.

5.4 Step 4: Does concurrency matter more than volume?

This is the fork that pushes teams toward capacity-based pricing, and it’s the one most teams ignore until it’s too late.

If your system’s worst failures occur when many users act at the same time, peak hours, batch jobs, synchronized workflows, then total usage is not your real problem.

Concurrency is.

In those systems, pricing based purely on usage will always undercharge the most expensive scenarios.

You’ll make money on average and lose money at the moments that matter most.

Capacity-based pricing is uncomfortable because it forces explicit limits. It requires you to say, “This is how much throughput you get,” instead of pretending capacity is infinite.

But for systems where latency, responsiveness, or guaranteed availability matter, it’s the only honest choice.

5.5 Step 5: How stable is the system today, really?

Teams love to price based on where they want the system to be.

Pricing must be based on where the system is.

If your AI still varies significantly in output quality, if it requires retries to reach acceptable answers, if it degrades under load, or if it relies on heavy guardrails to stay safe, outcome-based pricing is a trap.

You will spend more compensating for failures than you earn from successes.

Stability earns pricing power. It cannot be assumed.

This is why many successful AI companies migrate pricing models over time. They start with hybrid or usage pricing, invest heavily in stability, and only then introduce outcome-based components once failure rates are low enough to be economically tolerable.

Skipping that sequence is how companies bankrupt themselves while trying to appear customer-friendly.

5.6 Putting the decision tree together

When you combine these questions, the decision tree becomes clearer:

If users understand cost drivers and value immediate efficiency → usage-based

If users need freedom to explore and costs vary widely → hybrid

If outcomes are clear, narrow, and reliable → outcome-based

If concurrency, latency, or availability drives cost → capacity-based

Most products don’t fit neatly into one bucket, which is why hybridization happens. But even hybrids must have a dominant logic. You cannot serve four masters at once.

5.7 The internal question most teams avoid

Here’s the question that separates experienced teams from naive ones:

“Which users do we want to be expensive?”

Every pricing model makes someone expensive. Heavy users. Bursty users. High-stakes users. Enterprise users. The mistake is pretending that pricing can make everyone equally profitable.

It can’t.

The goal is not fairness. It’s sustainability.

If your pricing model makes your most demanding users your least profitable ones, you’ve built a time bomb.

5.8 Pricing as an evolving system, not a one-time decision

One final, often overlooked point: AI pricing should not be static.

As systems mature, cost variance shrinks. Routing improves. Context gets tighter. Failure rates drop. These improvements unlock new pricing options that were impossible earlier.

Teams that survive plan for this evolution. They don’t lock themselves into pricing models that only work at one stage of maturity.

They treat pricing like architecture: something that must adapt as reality changes.

5.9 The real purpose of the decision tree

This decision tree is not meant to give you a “correct” answer.

It’s meant to force alignment between:

system behavior

user psychology

cost variance

business survivability

If those four things are not aligned, no pricing model will save you.

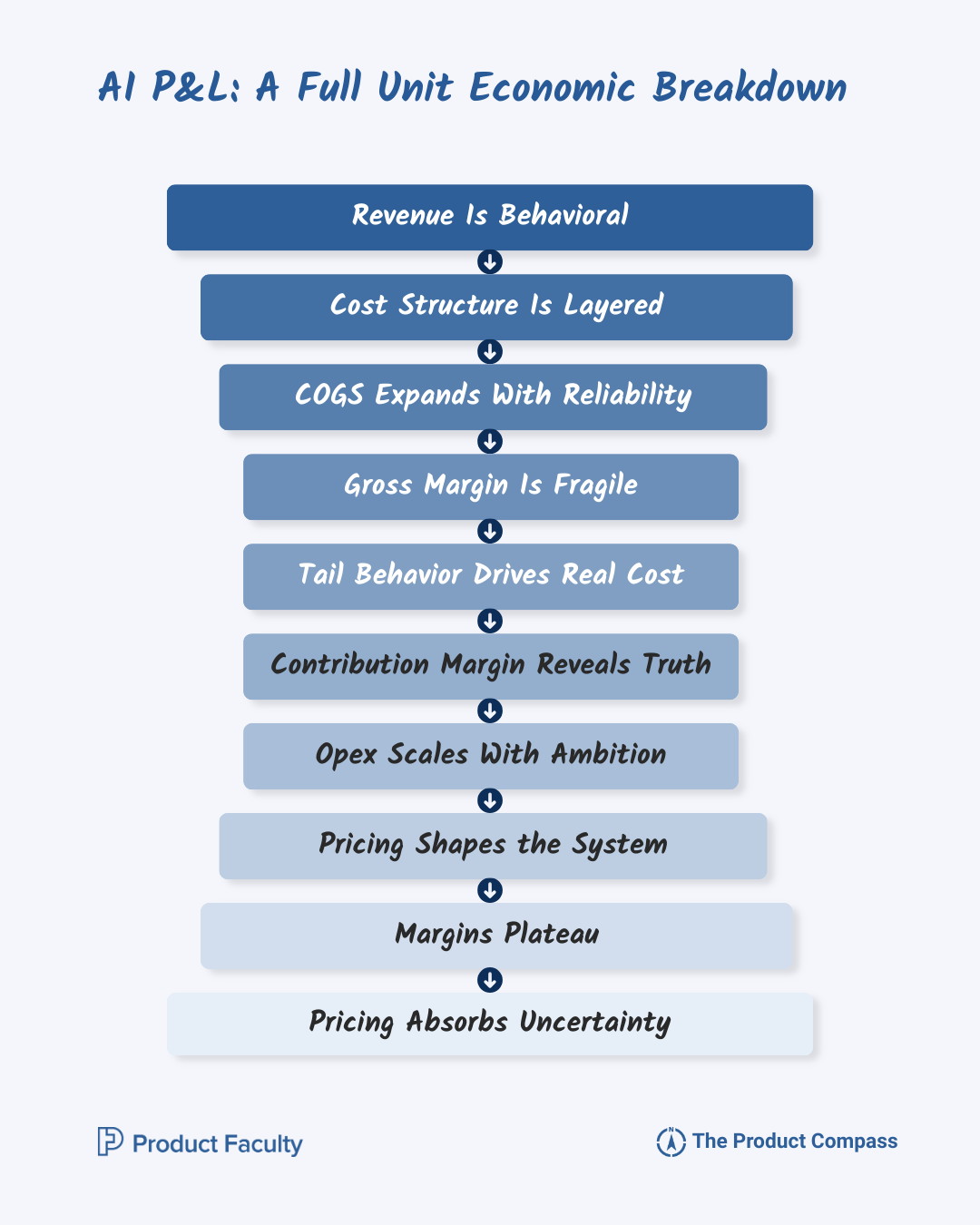

6. AI P&L: A Full Unit Economics Breakdown

If there is one place where AI optimism goes to die, it’s the P&L.

Not because AI can’t be profitable, but because most teams bring a SaaS mental model into a system that behaves nothing like SaaS.

They look at revenue growth, glance at token spend, see a decent gross margin, and assume it will improve with scale.

Then scale arrives and margins get worse.

To understand AI unit economics, stop thinking in averages and start thinking in scenarios. AI P&L is not about a typical day. It’s about your worst reasonable day, because that’s what your pricing must survive.

6.1 Revenue in AI is behavioral, not static

In SaaS, revenue is relatively clean. You sell seats, tiers, or contracts. Usage doesn’t usually change revenue meaningfully month to month.

In AI, revenue is elastic. It stretches and compresses based on how users behave.

Even subscription-heavy AI products have revenue that depends on:

whether you hit usage thresholds

whether overages trigger

whether premium tiers are actually used

whether customers churn after cost surprises

This means revenue forecasting is less about counting customers and more about understanding behavior distributions.

Two customers on the same plan can produce radically different revenue outcomes depending on whether your pricing model captures variance or ignores it.

This is why AI businesses that look healthy on MRR charts can still be economically fragile. MRR hides behavioral volatility.

6.2 COGS is not “model cost”

This is the single most common mistake teams make.

They treat COGS as inference cost and maybe add a little infrastructure overhead. Everything else gets pushed into “engineering” or “platform” expenses.

That accounting fiction feels convenient — until margins disappear.

Real AI COGS includes:

inference (across routed models)

retrieval and storage

orchestration overhead

retries and fallback paths

concurrency provisioning

monitoring, evaluation, and logging

incident mitigation when things go wrong

Some of these costs scale with usage. Others scale with importance, reliability expectations, or peak load. All of them belong in COGS if they are required to deliver the product promise.

When teams exclude these layers, they don’t make margins better. They just make margins invisible.

6.3 “We use LLM APIs, so why do concurrency costs matter?”

This is a fair question.

When you rely on APIs, you don’t manage GPUs directly. But you still pay for parallel demand. You just pay in second-order effects, not as a line item called “infrastructure.”

When many users hit your system at the same time, concurrency shows up as:

higher cost per successful outcome because retries and fallback calls spike

stricter rate limits that force slower responses, queues, or routing to heavier models

worse latency during peak windows, which triggers more abandonments and more “try again” behavior

usage spikes and overages that happen precisely when demand is highest

For example, if many users trigger complex workflows at the same time, the system doesn’t get “a little more expensive.” It behaves differently.

Requests take longer. Timeouts happen more often. Retries increase. Routing shifts. What looked like a cheap average becomes an expensive peak.

Even with APIs, you are still pricing for peak behavior, not average behavior. Ignore that, and your P&L will remind you.

6.4 Gross margin in AI is fragile by default

In SaaS, gross margins tend to improve with scale. Infrastructure amortizes. Support costs per user fall. Systems stabilize.

In AI, gross margin can move the other way.

As usage grows:

tasks get more complex

retries increase

concurrency spikes sharpen

stability investments increase

routing shifts to higher-cost models

Unless pricing tightens alongside growth, margins compress.

This is why “we’ll fix margins later” is such a dangerous belief in AI. Later often means after users have learned expensive behaviors and expect them to be free.

Healthy AI businesses design pricing so that gross margin is resilient to success, not dependent on it.

6.5 The myth of average cost per request

Average cost per request is a comforting metric. It smooths out spikes and makes systems feel manageable.

It is also deeply misleading.

AI systems are dominated by tail behavior. A small percentage of requests generate a large percentage of cost. Those requests often correspond to:

heavy users

enterprise workflows

complex edge cases

synchronized demand

If pricing doesn’t monetize those tails, they become loss leaders.

This is why experienced teams model:

p90 cost

p95 cost

peak concurrency cost

worst-case burst scenarios

If your pricing model doesn’t survive those scenarios, it doesn’t survive reality.

6.6 Contribution margin matters more than gross margin

Another subtle shift in AI economics is the importance of contribution margin.

Gross margin tells you whether the product can exist. Contribution margin tells you whether growth is healthy.

In AI, some users may be gross-margin positive but contribution-margin negative once you factor in:

support burden

customization

reliability demands

manual intervention

Pricing models that look good at the aggregate level can hide segments that quietly drain resources.

This is why many AI companies eventually introduce differentiated pricing not just by usage, but by support level, reliability guarantees, or customization. These are not upsells; they are cost recoveries.

6.7 Opex doesn’t behave the way teams expect

In SaaS, Opex often scales slower than revenue. In AI, certain Opex categories scale with ambition:

If you want higher accuracy, you pay for evaluation.

If you want enterprise trust, you pay for audits and compliance.

If you want safety, you pay for monitoring and review.

These are not optional expenses once the product becomes serious. They are structural.

Pricing that ignores these realities forces the business to subsidize ambition indefinitely. That’s not strategy; it’s wishful thinking.

6.8 The hidden coupling between pricing and engineering roadmaps

Here’s a reality most teams discover too late: pricing decisions constrain engineering decisions.

If pricing is tight and margins thin, engineers are forced to optimize aggressively, sometimes at the expense of quality. If pricing leaves room, teams can invest in stability, tooling, and long-term improvements.

This creates a feedback loop. Weak pricing forces short-term optimization, which increases system brittleness, which increases retries and failures, which increases cost — making pricing even weaker.

Strong pricing gives teams breathing room to improve systems, which reduces variance, which improves margins over time.

Pricing is not just about revenue. It shapes the entire product development trajectory.

6.9 Why AI businesses must plan for margin plateaus

One of the most counterintuitive insights in AI economics is that margins often plateau before they improve.

As systems mature, you invest heavily in stability, safety, and reliability. These investments increase cost before they reduce variance. For a period of time, margins may stagnate or even dip.

Teams that expect linear improvement panic during this phase and cut corners prematurely. Teams that expect the plateau price for it and survive long enough to reap the benefits.

This is another reason why conservative pricing early on matters. It gives you room to endure the messy middle.

6.10 The role of pricing in absorbing uncertainty

The central purpose of pricing in AI is not maximization. It is absorption.

Absorbing:

cost variance

usage spikes

reliability investments

behavioral unpredictability

When pricing does this well, the business feels calm even when the system is complex. When it does this poorly, every spike feels existential.

You cannot remove uncertainty. You can only decide where it lives: with the company or with the customer.

Healthy businesses share it explicitly. Unhealthy ones absorb it silently until they break.

6.11 The P&L question that matters most

If there is one question every AI PM and founder should ask regularly, it’s this:

If usage doubles tomorrow, does margin improve, stay stable, or get worse?

If the honest answer is “worse,” pricing is not aligned with reality.

Growth that destroys economics is not growth. It’s deferred failure.

7. Conclusion

AI pricing is not about maximizing revenue.

It’s about keeping the system honest.

Honest about what it costs to run, how it behaves under pressure, and what you can reasonably promise.

SaaS taught you to remove friction at all costs. AI teaches the opposite lesson: some friction is necessary for the system to survive.

If you take one idea away from this entire newsletter, let it be this:

Price for your worst reasonable day, not your average day.

Models will get cheaper. Tooling will improve. But variance won’t disappear. The edges will still be unpredictable.

Pricing is how you decide who absorbs that unpredictability.

Choose wisely, because your system is already making the trade-offs for you.

8. AI Cost Glossary

What actually drives your AI bill, why it matters, and the mistake to avoid.

8.1 Inference cost

What it is: The cost of running the model to generate an output.

Why it matters: Every time the model “thinks,” you pay. Unlike SaaS, this cost never goes to zero.

Common mistake: Thinking inference cost is the only AI cost.

8.2 Token cost

What it is: The unit used to price model input and output length.

Why it matters: Longer prompts and longer answers cost more, but tokens are only the visible part of the bill.

Common mistake: Optimizing tokens while ignoring everything else that multiplies them.

8.3 Context cost

What it is: The cost impact of what you feed the model before it answers (instructions, memory, documents, history).

Why it matters: Context grows quietly over time. Bigger context means higher cost, slower responses, more variance.

Common mistake: Adding “just one more rule” forever.

8.4 Retrieval cost

What it is: The cost of fetching relevant information before inference.

Why it matters: Bad retrieval doesn’t just cost once. It inflates context and inference downstream.

Common mistake: Retrieving too much “just in case.”

8.5 Orchestration cost

What it is: The cost of coordinating multiple model calls, tools, agents, and steps in a workflow.

Why it matters: One action often triggers many calls behind the scenes.

Common mistake: Counting one user request as one model call.

8.6 Retry cost

What it is: Extra cost when the system reruns a call due to low confidence, errors, or validation failures.

Why it matters: Retries multiply costs silently.

Common mistake: Adding retries for safety without pricing for them.

8.7 Routing cost

What it is: The cost impact of deciding which model handles which task.

Why it matters: Routing everything to the biggest model feels safe and destroys margins.

Common mistake: Using one model by default instead of routing.

8.8 Parallelism (concurrency) cost

What it is: The cost impact of many requests happening at the same time.

Why it matters: AI systems are priced for peak demand, not average demand.

Common mistake: Ignoring concurrency because “we don’t manage GPUs.”

8.9 Peak load cost

What it is: The cost of handling your busiest moments.

Why it matters: Most AI systems feel cheap until everyone uses them at once.

Common mistake: Pricing for average usage instead of worst-case days.

8.10 Evaluation cost

What it is: The cost of checking whether output is correct, safe, or usable.

Why it matters: Serious AI products pay continuously to monitor quality.

Common mistake: Treating evaluation as optional overhead.

8.11 Human-in-the-loop cost

What it is: The cost of humans reviewing, correcting, or approving outputs.

Why it matters: The more critical the use case, the more humans you need.

Common mistake: Assuming humans are temporary.

8.12 Failure cost

What it is: The hidden cost of wrong answers: rework, support tickets, refunds, trust erosion.

Why it matters: Failures often cost more than successful inferences.

Common mistake: Ignoring downstream business impact.

8.13 COGS

What it is: Everything required to deliver one unit of AI value.

Includes: Inference, retrieval, orchestration, retries, monitoring, evaluation, capacity pressure.

Common mistake: Treating AI like SaaS with near-zero marginal cost.

8.14 Gross margin

What it is: Revenue minus AI delivery costs.

Why it matters: In AI, margins can shrink as usage grows if pricing ignores variance.

Common mistake: Assuming scale automatically improves margins.

8.15 Contribution margin

What it is: Profitability of a specific user or segment.

Why it matters: Your most active users may be your least profitable.

Common mistake: Only looking at averages.

8.16 Variance

What it is: How unpredictable AI costs and behavior are across users and scenarios.

Why it matters: Variance, not averages, destroys AI businesses.

Common mistake: Pricing for “typical” behavior.

8.17 Behavior-driven cost

What it is: Costs created by how you interact with the system, not just how many users exist.

Why it matters: AI costs scale with behavior, not headcount.

Common mistake: Treating engagement as universally good.

8.18 The one rule to remember

If you remember nothing else from this glossary, remember this:

AI pricing fails when it ignores how AI behaves under real user pressure. Tokens are not the problem. Variance is.